[Guest post] Retromark Volume VI: the last six months in trade marks

It’s time for the sixth volume of Retromark, Darren Meale of Simmons & Simmons’ rundown of notable trade mark cases over the past six months.

If you only read one legal document this month, read the latest Brexit Withdrawal Agreement, and go quietly weep for days gone by when the UK was a serious country. If you read two legal documents, please consider my latest summary of cases of interest, which now follows.

1. Yes, no, maybe, can you repeat the question?

Does the mark ZARA TANZANIA ADVENTURES for travel and tourism take unfair advantage of fashion chain ZARA’s reputation for clothing?

No, said the EUIPO’s Opposition Division.

No, said the EUIPO’s Board of Appeal.

Yes, said the EU General Court.

Despite Zara’s reputation being for goods which are a world apart from the applicant’s services, the General Court seemed persuaded by the somewhat vague evidence of a trend that fashion brands are or might expand into adjacent markets such as foodstuffs, restaurants and hotels. Fashion, apparently, is everything.

I cover the Claridge’s case below, which I say is a classic case of extended protection in action. Inditex is also an extended protection case, but in my view it’s much more of a classic case of the EU trade mark system doling out almost coin-toss decisions as a case scales the appeal chain. Any seasoned EU trade mark litigator will tell you this case could have gone the opposite way several other days of the week. IPKat here.

2. Beauty Bay: the challenge of the judicial assessment of likelihood of confusion

Beauty Bay and Dotcom Retail v Benefit Cosmetics [2019] EWHC 1150 (May 2019)

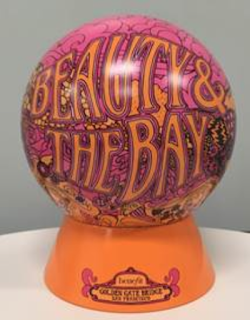

Is the mark BEAUTY BAY infringed by the use of BEAUTY & THE BAY for identical goods – namely cosmetics and the retail thereof? No, says the UK High Court. Reading the judgment without knowing the ending, you might be forgiven for expecting that the claimant was going to win. The marks are evidently very close visually – the differences are “& THE”, both elements of very low distinctiveness. The goods are identical. The defendant’s argument that it was not making use of its name as a brand, but in a decorative fashion, with the only brand being the much smaller use of BENEFIT on the base of the product, was rejected. Benefit also argued that BEAUTY & THE BAY was a “limping” mark, one which would not be recognised as a badge of origin given the strength of the BENEFIT mark – this too was rejected. The judge even accepted that the circumstances of the case meant it was unlikely that actual confusion would have come to the attention of the parties.

|

| The defendant’s product. |

Despite a detailed analysis of all the points, the judge’s actual evaluation of the likelihood of confusion is set out in two short sentences (at paragraph 60), in which he essentially says (I am paraphrasing) “it is for me to assess, taking into account all relevant circumstances … my assessment is [no drum roll] no likelihood of confusion”. The judge also dismissed a reputation-based claim on the basis that consumers would not link the two marks.

I should not be too critical of the Deputy High Court Judge’s (Mr Roger Wyand QC) apparently abrupt conclusion. Ultimately, likelihood of confusion is one of those “in the balance” assessments which a judge just has to decide, one way or the other. But this decision feels wrong – it feels as if it would be a more reasonable use of discretion to decide the case in the claimant’s favour, especially after dismissing essentially all of the defendant’s other arguments. But, alas, it went the other way. IPKat here.

3. Disclaimers: not really something to bother with anymore under EU trade mark law

Patent- och registreringsverket v Mats Hansson Case C-705/17, CJEU (June 2019)

A disclaimer is an odd thing: “it is part of my mark, but please ignore it”. Disclaimers were available under the EUTM system, but not since 2015. They are permitted in the UK (but we do not see them often), and in other EU Member States, such as Sweden, where this case originated, as well as elsewhere (such as in the US). The Swedes asked the CJEU what the effect should be of a disclaimer which expressly excluded an element of a mark. The particular example considered was the disclaimer, “registration does not give an exclusive right over the word RoslagsPunsch” in a figurative mark containing that word. The word combined a region of Sweden (Roslags) with one of the goods covered by the registration (Punsch).

There were three options: (1) exclude the disclaimed element from the analysis of likelihood of confusion; (2) consider it, but presuppose that the element has less importance; or (3) ignore the disclaimer and follow established case law on how to assess the likelihood of confusion – basically the global appreciation test having regard to all the factors.

The CJEU went for option (3): a disclaimer cannot exclude an element from the likelihood of confusion analysis, and it cannot “in advance and permanently” limit the importance of the element in the analysis. So, in essence, not much point in a disclaimer. IPKat here.

4. Like brands, only infringements? Aldi make-up lookalike infringes copyright

Islestarr Holdings Ltd v Aldi Stores Ltd [2019] EWHC 1473 (June 2019)

A first for Retromark: a case not about trade marks. Lookalike products are often the subject of attempts to assert trade marks or make out passing off, but in this case against supermarket Aldi the claimant won by relying on copyright.

The products were make-up palettes. The image below from the judgment compares them. The claimant’s product sold for £49 while Aldi’s knock-off sold for £6.99. Aldi were alleged to have copied the starburst design on the top of the palette and the design which was “embossed” onto the make-up powder itself.

The claimant applied for summary judgment and won. The judge held that copyright could subsist in the powder design even if it were temporary, just as a bespoke wedding cake (later to be eaten) could be protected. Both designs were original works and deserved copyright protection. There was evidence of access/awareness and substantial similarity, shifting the burden to Aldi to show there was no copying – which it failed to do.

The judge therefore concluded that Aldi had no real prospect of successfully defending the claimant's claim for copyright infringement of each design and allowed the application for summary judgment. More from the IPKat here.

5. Revokey McRevokeface for McDonalds McMark

Supermac's v McDonald's Cancellation no. 14787C, EUIPO (July 2019)

I covered an earlier chapter of this burger battle in Volume V, in which poor evidence led to the loss of a BIG MAC EU trade mark registration. This time it was the Mc prefix under attack, and an EUTM was lost for a range of food products plus restaurant services, surviving for meat sandwiches and chicken nuggets.

This was a non-use action, so it all came down to the evidence. In the BIG MAC case, that evidence was pretty poor. McDonald’s looks to have done better here, although the EUIPO still remarked that the documents provided were “not particularly extensive”.

The EUIPO concluded that there was no evidence of Mc being used alone, only with other words – like McRIB. That meant the use would only count if the addition of other elements did not alter the distinctive character of the Mc mark. The EUIPO concluded that the distinctive character was altered where the use was as part of MCDONALD’S, BIG MAC and MCFLURRY. So the mark was lost for the goods and services to which those marks were applied – such as restaurant services. The position was different for McMUFFIN, McNUGGETS and so on, owing to those additional elements being descriptive.

Although a case turning on the evidence, it does give a useful illustration of the “altered distinctive character” test for determining whether the use of one mark counts as use of another. It might also be regarded as a generous decision when one considers that McDonald’s no doubt registered Mc motivated by a desire to seek a monopoly on all Mc-formative marks. I am not saying this decision supports the conclusion that McDonald’s has secured such a monopoly, but there would be profound consequences if it were possible to register a two letter mark and then be able to enforce it against all other marks starting in those two letters, even if the mark was never used alone.

Some not completely inaccurate coverage from the BBC here.

6. FREE PRINTS for free prints, yes this really is a passing off claim

Planet Art v Photobox [2019] EWHC 1688 (July 2019)

The claimant sold photo prints via an app called FREEPRINTS. The defendant did the same via an app called PHOTOBOX FREE PRINTS. The claimant sued for passing off and applied for an interim injunction, offering to allow the defendant only to make “genuinely descriptive use of the phrase ‘FREE PRINTS’”.

The claimant’s case was that what would have been a descriptive name had acquired a secondary meaning, granting it protection under passing off. The defendant argued that even if that were proven, it had distinguished its use of FREE PRINTS from the claimant’s by adding PHOTOBOX. The judge applied the American Cyanamid principles to determine whether, pending trial, an injunction should be granted. In this Kat’s view the claimant must surely face an uphill struggle, but the judge was not satisfied that she could say there was no “serious issue to be tried”, the first of the American Cyanamid principles. The judge also concluded that damages would not be an adequate remedy on either side. So where did the balance of convenience lie? The judge held that it was in favour of refusing the interim injunction. She took into account her view that the defendant would likely suffer the greater damage and what she described as some “material weaknesses” in the claimant’s case – obviously not large enough for her to rule there was no serious issue, but enough to tip the balance against the claimant.

So far as I know this case is still going – but I’ll bet you a thousand free prints the claimant is not going to come out on top. IPKat here.

7. Can Claridge Candles Cause Confusion?

Claridge's Hotel v (1) Claridge Candles (2) Denise Shepherd [2019] EWHC 2003 (July 2019)

Claridge’s is a famous London hotel operating for more than 150 years. Some of its suites sell for more than £3,500 a night. The defendants sold CLARIDGE candles, named after Ms Shepherd’s address, 5 Claridge Court. The hotel won. There is nothing revolutionary about this case, but it is a classic example of a reputation-based claim under section 10(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994. The hotel could not rely on its registration for similar goods because it had not used them, instead it succeeded by establishing that the defendants were taking unfair advantage of its reputation for hotel (and other) services. It achieved this notwithstanding the fact that the coincidence in name was not deliberate, largely because the judge believed that consumers would confuse the defendants’ goods with the hotel’s services even though they were different. Confusion is not a requirement of 10(3), but it certainly helps. The judge also found passing off.

More details on the NIPC Law blog. Current offers at Claridge’s here, in case you can’t quite stretch to £3.5k a night.

8. Hasbro hindered as MONOPOLY monopoly malfunctions massively

MONOPOLY Case R1849/2017-2, EUIPO Board of Appeal (July 2019)

Hasbro filed multiple EU trade marks for the iconic board game, MONOPOLY. The first was in 1996, then another in 2008, then two more in 2010. There was a lot of overlap, although the fourth application added additional goods and services. Hasbro’s attempt to explain the rationale for these multiple overlapping filings did not convince the EUIPO Board of Appeal, which concluded that there was “no other commercial logic” for the re-filings beyond getting around the risk that the older marks would be vulnerable to attack for non-use. The Board of Appeal therefore found that the re-filings were in bad faith in so far as they covered duplicate goods and services, but the non-duplicates parts of the marks were unaffected and remained valid. Hasbro has appealed to the General Court.

I do not read this case as forbidding duplication in later filings in any circumstances, but the applicant needs to be able to justify by reference to commercial logic. Evergreening is not on, and the EU trade mark system remains a use-it-or-lose-it system. IPKat here. See here for a Buzzfeed take on why Monopoly isn’t a great game, and why you’re better off trying Settlers of Catan. Or even Cones of Dunshire.

9. Target your website at the UK, get sued in the UK – an EU jurisdiction question answered

Making its fourth appearance, I’ve covered this case in Volumes I, II and V as it made its way from the IPEC to the Court of Appeal to an Advocate General’s opinion.

This is all about websites targeting consumers in particular places. The scenario being considered was this: the defendant was established and domiciled in territory A (Spain). It offered infringing goods on its website and targeted consumers in territory B (UK). Did the B (UK) courts have jurisdiction to hear the claim for infringement of the EUTM in question? Essentially following the lead set by the Advocate General, the CJEU answered in the affirmative.

The simple “yes” answer belies the complexity that underlies this, and perhaps all, questions of international jurisdiction. To come to its decision, the Court of Justice had to navigate through a number of conflicting statutory provisions and a bunch of past CJEU case law. In reaching its conclusion, the Court noted that an alternative interpretation of the jurisdictional rules which turns on where the allegedly infringing offers for sale were placed online would be open to abuse by the alleged infringer, who could simply set up its website outside of the EU and avoid liability.

So now we know that if you target a place online, you can get sued there. The case will return to the UK’s IPEC for a final decision on the facts. IPKat here.

10. SkyKick: an opinion that will change the practice of trade marks forever, or maybe not

Sky v SkyKick Case C‑371/18, CJEU (October 2019)

This case needs little introduction – I covered it in Volume II and Volume III. Advocate General Tanchev has now given his keenly awaited opinion, which the Court of Justice of the EU may or may not follow when it later gives its judgment. The opinion is worth reading in full and is already covered on the IPKat here, so I’m going to be brief. AG Tanchev’s key conclusions are as follows:

- The presence of unclear or imprecise terms in a list of goods and services may lead to refusal or invalidity of a mark on the basis that the mark is contrary to public policy (Article 7(1)(f) EUTMR).

- “Computer software” is one such term. Registration of a mark for this term is unjustified and contrary to the public interest. The monopoly granted is of “immense breadth” and just too broad. The AG thought it difficult to see why the same conclusion should not apply to “telecommunications services” or “financial services”.

- It is bad faith to apply for goods and services with a deliberate intention to acquire rights the applicant has no intention to use. If this were not so, the system would be open to abuse. A reasonable commercial rationale for seeking protection in light of a use or intended use should suffice to avoid a bad faith finding.

- A registration may be declared partly invalid where the bad faith only applies to some goods and services. Previous General Court authority suggesting an all or nothing approach to invalidity for bad faith is wrong.

There’s no doubt that, if the CJEU follows this, the judgment will have a very significant impact on the practice of EU trade marks, including in the UK. However, the last bullet may substantially limit that impact, because the only penalty for an overly broad specification will be the loss of the offending terms – not the whole thing. The opinion does not offer an incentive for broad filers to really narrow down what they file going forward.

There is a concern for those who have registrations for the broad terms and only the broad terms (without also having coverage for more specific terms (eg, “software” alongside “software for spellchecking”). Will all those registrations (and there must be thousands) be invalid? Or will the IPOs offer an opportunity to amend and narrow down?

That’s all for now.

Thanks to my colleague Sarah Turner for helping compile the Volume’s featured cases.

***

Volume I – April 2016 to March 2017

Volume II – March 2017 to September 2017

Volume III – November 2017 to April 2018

Volume IV – May 2018 to October 2018

Volume V – November 2018 to March 2019

[Guest post] Retromark Volume VI: the last six months in trade marks

![[Guest post] Retromark Volume VI: the last six months in trade marks](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgPQ884cIWSDCW8FMi8A02VFm9Efo8sNSd5qW4YMREsSEWZ71OvO6XrrfJTNatVRJRb5GcuS0kW50mSjEKM7X2-XUxFF9D3UlnH8Xy_XDRcT9Jnepz4E3vcK1euiERAy1hAfcG9AOaPFciR/s72-c/Screenshot+2019-10-24+at+17.09.12.png) Reviewed by 0x000216

on

Thursday, October 24, 2019

Rating: 5

Reviewed by 0x000216

on

Thursday, October 24, 2019

Rating: 5

![[Guest post] Retromark Volume VI: the last six months in trade marks](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgPQ884cIWSDCW8FMi8A02VFm9Efo8sNSd5qW4YMREsSEWZ71OvO6XrrfJTNatVRJRb5GcuS0kW50mSjEKM7X2-XUxFF9D3UlnH8Xy_XDRcT9Jnepz4E3vcK1euiERAy1hAfcG9AOaPFciR/s72-c/Screenshot+2019-10-24+at+17.09.12.png) Reviewed by 0x000216

on

Thursday, October 24, 2019

Rating: 5

Reviewed by 0x000216

on

Thursday, October 24, 2019

Rating: 5