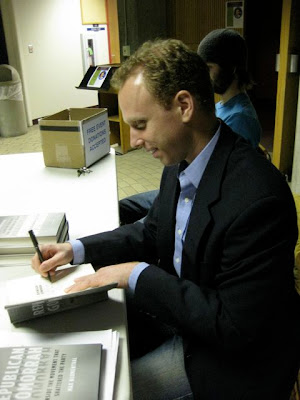

Max Blumenthal at University of Alaska Anchorage

Blumenthal adds pyschology into the analysis of the far right Christians in his book Republican Gomorrah. Last night he spoke about the book to a receptive audience in the art building at UAA.

He began talking about President Eisenhower's letter to a soldier who'd written to him. I'll just quote directly from his book, Republican Gomorrah:

For me, this is one of the more plausible narratives, one I've toyed with, though not in the depth Blumenthal has, to explain the angry shut minds that we've been seeing at anti-health care debates, on Fox News, etc.

From pop philosopher Eric Hoffer, Blumenthal goes to Erich Fromm, a German Jewish psychoanalyst and scholar, who fled Germany when the Nazis came to power and

I've written on this blog and elsewhere that I felt that much of the anger we see these days stems with the frustrations of a rapidly changing and difficult-to-understand new world that leaves many people feeling powerless - particularly those who in the past had relatively stable and privileged positions in society.

Blumenthal takes this premise as the jumping off point to examine the religious right, their leaders, and followers. He offers facts about the lives of the leaders and followers to show how they fit Fromm's model. A lot of people, scared by the choices of the modern world, reaching for father figures who explain the world in black and white, good and evil terms, and outline a path to a better worold.

Blumenthal is young, yet the talk - and I assume the book itself, which he outlined, and I've only skimmed - reveals a macro level understanding of American politics and society which he buttresses with lots of supporting details. We will hear a lot more from Blumenthal.

It's the kind of book that should be assigned reading for all people planning to attend a Teabagger event and all people who are thinking about attending a right wing Evangelical church service. Some are too far into denial to see themselves, but some are not so far gone that some flashes of light won't make it through to them. And there is also the danger of taken this as 'the truth' rather than as an explanation.

He began talking about President Eisenhower's letter to a soldier who'd written to him. I'll just quote directly from his book, Republican Gomorrah:

[Eisenhower's] experience in Europe had taught him that the rise of extreme movements could be explained only by the psychological yearnings and social needs of their supporters. He understood that these movements were not unique to any place or time. Authoritarianism could take root anywhere even in America. Eisenhower did not believe that an American exceptionalism immunized the country against the spores of extremism.

...throughout his presidency, Eisenhower clung to a short book that informed his view of the danger of extremist movements. He referred to this book in the first televised presidential press conference ever, distributed it to his friends and top aides, and cited its wisdom to a terminally ill World War II veteran, Robert Biggs, who had written him a letter saying he "felt from your recent speeches the feeling of hedging and a little uncertainty. We wait for someone to speak for us and back him completely if the statement is made in truth."

Eisenhower could have tossed Biggs's missive in a heap of unread letters his secretary discarded each day, or he could have allowed a perfunctory and canned response, but he was eager for an opportunity to expound on his vision of the open society. "I doubt that citizens like yourself could ever, under our democratic system, be provided with the universal degree of certainty, the confidence in their understanding of our problems, and the clear guidance from higher authority that you believe needed," Eisenhower wrote Briggs on February 10, 1959. "Such unity is not only logical but indeed indispensable in a successful military organization, but in a democracy debate is the breath of life."(pp. 5-6)

The president then opined that free societies do not necessarily perpetuate freedom; many citizens would be far more comfortable under a structure that provides rigid order and certainty about all aspects of life. "The mental stress and burden which this form of government imposes has been particularly well recognized in a little book about which I have spoken on several occasions," Eisenhower wrote. "It is 'The True Believer,' by Eric Hoffer; you might find it of interest. In it, he points out that dictatorial systems make one contribution to their people which leads them to tend to support such systems - freedom from the necessity of informing themselves and making up their own minds concerning these tremendous complex and difficult questions."(p. 6)[emphasis added.]

For me, this is one of the more plausible narratives, one I've toyed with, though not in the depth Blumenthal has, to explain the angry shut minds that we've been seeing at anti-health care debates, on Fox News, etc.

From pop philosopher Eric Hoffer, Blumenthal goes to Erich Fromm, a German Jewish psychoanalyst and scholar, who fled Germany when the Nazis came to power and

. . .published Escape from Freedom, a book illuminating the danger of rising authoritarian movements with penetrating psychoanalytical insight.

Writing after the Nazis had overrun Europe but before the entrance of the United States into World War II, Fromm warned, "there is no greater mistake and no graver danger than not to see that in our own society we are faced with the same phenomenon that is fertile soil for the rise of Fascism anywhere: the insignificance and powerlessness of the individual." (p. 8) [emphasis added]

I've written on this blog and elsewhere that I felt that much of the anger we see these days stems with the frustrations of a rapidly changing and difficult-to-understand new world that leaves many people feeling powerless - particularly those who in the past had relatively stable and privileged positions in society.

Those who could not endure the vertiginous new social, political, and personal freedoms of the modern age, those who craved "security and a feeling of belonging and of being rooted somewhere" might be susceptible to the siren song of fascism. For the fascist, the struggle for a utopian future was more than politics and even war - it was an effort to attain salvation through self-medication. When radical extremists sought to cleanse society of sin and evil, what they really desired was the cleansing of their souls. (p. 8)

Blumenthal takes this premise as the jumping off point to examine the religious right, their leaders, and followers. He offers facts about the lives of the leaders and followers to show how they fit Fromm's model. A lot of people, scared by the choices of the modern world, reaching for father figures who explain the world in black and white, good and evil terms, and outline a path to a better worold.

Blumenthal is young, yet the talk - and I assume the book itself, which he outlined, and I've only skimmed - reveals a macro level understanding of American politics and society which he buttresses with lots of supporting details. We will hear a lot more from Blumenthal.

It's the kind of book that should be assigned reading for all people planning to attend a Teabagger event and all people who are thinking about attending a right wing Evangelical church service. Some are too far into denial to see themselves, but some are not so far gone that some flashes of light won't make it through to them. And there is also the danger of taken this as 'the truth' rather than as an explanation.