"Read all about it!" Court rules web is permanent, newspapers are ephemeral

|

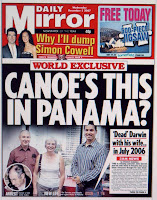

| Daily Mirror: from today's fresh news ... |

Grisbrook had provided photographs for MGN for a number of years, without a written contract, being paid when his photographs were used. MGN archived the photographs it used; any subsequent use by MGN entitled the photographer to a further fee. It was conceded that Grisbrook licensed MGN to use his photos in this way while retaining copyright in them, though there was some dispute as to how far this licence extended. In particular, did it extend to the use of Grisbrook's works on MGN's websites?

|

| ... to tomorrow's fish and chip wrapper |

Grisbrook was not best pleased with this and went to court, arguing that any reproduction of already-published material constituted an infringement of his copyright and was therefore a breach of the undertaking. No, said MGN: the consent order was not intended to cover the reproduction of photographs which were contained in already-published newspapers and should be construed accordingly. MGN further argued that, even if the undertaking was unlimited and included such infringements, no infringement had taken place or could take place as the licence granted by Grisbrook had to be treated as extending to the subsequent reproduction or use of published material. Patten LJ concluded that MGN had infringed Grisbrook's rights but refused the application to commit MGN for contempt. In his view

* The real issue between the parties was whether the operation of the back issues websites amounted to an infringement of Grisbrook's copyright in the photographs contained in those issues: did MGN's licence impliedly extend to the storage of and access to Grisbrook's photos as they appeared in the back issues?

* Since such an implied licence derogated from or relaxed the copyright owner's statutory rights, it was for MGN to justify the basis for extending the licence to cover what would otherwise be separate acts of infringement.

* The compilation of a database and its use for archival purposes might be so justified, but the exploitation of Grisbrook's photos through the back issues websites seemed to be a different kind of operation, one that was not contemplated at the time the licence was granted and could not be said to have been necessary to regulate the rights of the parties at that time. MGN's operation of the back issues websites accordingly infringed Grisbrook's copyright.

* MGN was entitled to take a different view on this difficult question, and disputes of this sort should not be resolved through committal proceedings. The dangers inherent in generally worded injunctions or undertakings not to infringe a patent or copyright had long been recognised and could often lead to a further round of litigation in order to determine whether an infringement had occurred. Nor was the infringement point which Grisbrook was arguing a point that featured in the actions which led to the consent order. A party who argues in good faith that his conduct did not amount to an infringement should not ordinarily be penalised by a fine or sequestration in the event of failure merely because an applicant had chosen to use committal proceedings rather than an ordinary claim to resolve the issue.

* Although the operation of the back numbers websites did infringe Grisbrook's copyright in his photographs, those rights could be adequately protected by a declaration to that effect.MGN appealed and, today, the Court of Appeal (The Chancellor himself -- Sir Andrew Morritt, Lord Justice Leveson and Lord Justice Etherton) [2010] EWCA Civ 1399, dismissed the company's appeal. Delivering a judgment with which his colleagues agreed, the Chancellor held as follows:

"... it is common ground that there was a separate contract between Mr Grisbrook and MGN in relation to the reproduction of each photograph produced by the former and submitted to the latter for publication in its newspapers. The contract was formed by conduct, no terms were reduced to writing nor is there any evidence that there was any express oral agreement in relation to any of them. It follows that the broad principle to be applied is that ..."...the engagement for reward of a person to produce material of a nature which is capable of being the subject of copyright implies a permission or consent or licence in the person giving the engagement to use the material in the manner and for the purpose in which and for which it was contemplated between the parties that it would be used at the time of the engagement."

... the application of this principle gave rise to a licence to reproduce the photograph in the Daily Mirror and to add the photograph, both separately and as part of the published newspaper, to the MGN archive and picture store. A second or subsequent use might be made of the photograph but on terms that MGN paid Mr Grisbrook a further fee. ... It is accepted ... that the licence extended to reproducing the photograph and newspaper in a microfiche and, later, in an electronic form as part of the MGN archive. It is not suggested that Mr Grisbrook was not entitled to revoke the licences ... All his photographs have now been removed from MGN's archive. But such revocation extended only to future use. It could not retrospectively constitute the previous publications of Mr Grisbrook's photographs in the Daily Mirror as infringements. All those publications remain in the MGN archive and copyright in them is vested in MGN.

There are many reported cases in which the issue arose as to whether a written licence extended to subsequent forms of technology. That has depended on the form of words used and has not, for the most part, been limited to the technology which the parties contemplated at the time they entered into the relevant licence. ... In those cases the modern jurisprudence on the interpretation of written agreements ... may need to be re-examined. But this appeal does not concern a written contract. The implication is not to be made into a written contract from the words used in their context but into a contract by conduct "from the manner and for the purpose in which and for which it was contemplated between the parties that it would be used at the time" the contract was made.

... In relation to the application of that principle the area of disagreement is limited. In paragraph 65 of his judgment Patten LJ recognised that the application the correct principle gave rise to a licence to copy Mr Grisbrook's photographs and any other infringing act in relation to the compilation of the MGN database and its use for archive purposes. The dispute relates to the commercial exploitation of that database by means of the three websites to which I have referred.

...

The internet: an early screen shot

shows the medium's permanence

For my part I would agree that the operation of the website can be regarded as further delivery of the original, but not that it can only be so regarded. A website operates over a global area, its coverage is greatly in excess of anything MGN could have reached with hard copy newspapers. It enables a member of the public to read it before deciding whether he wants a hard copy and the production of hard copies by the public far in excess of anything MGN could have produced. The extent of the market and the costs incurred in reaching it are quite different to those of the hard copy newspapers of the past. There is no need to emphasise the differences further. The suggestion that an intention may be imputed to Mr Grisbrook and MGN from their conduct in relation to Mr Grisbrook's photographs in the period 1981 to 1997 that MGN should be entitled without further charge to exploit the copyright of Mr Grisbrook in his photographs by inclusion on their websites is, to my mind, unacceptable. Newspapers are essentially ephemeral and, save for the enthusiastic collector, retain no long lasting status: the parties will have intended that they would be treated as daily papers are generally treated, that is to say, read and replaced with the following day's edition. To incorporate the pictures into the website is to provide a permanent and marketable record easily available world-wide which could well reduce the value of the further use by Mr Grisbrook of the photographs over which it is common ground he possesses the copyright. That is why, to my mind, this is not just a question of degree but of kind ...".The IPKat says, one can hardly imagine a clearer statement: what we term "hard copy" is actually ephemeral, the creature of a moment, almost instantly irrelevant, while the presence of a work on a server from which it can be accessed by the internet is a sign of its permanence. The implications of this decision may take a little while to appreciate, but the IPKat will be surprised if these dicta are not cited with increasing frequency in all manner of disputes as to not just the interpretation of licences but the nature of damage for wrongful use and the calculation of quantum.