Of hockey sticks and disk brakes: claim breadth and added matter

A katpat goes to Paul England (Taylor Wessing LLP) for writing up an appellate decision published earlier this week on added matter in amended patents which offers a bit of tempting speculation about the breadth of claims.

Merpel, who has been admiring Louis Wain's "Hockey", above, was a little anxious that all those cats might be hurting themselves and each other when playing so rough a sport. Then it occurred to her that even a bruising game of hockey might turn out less painful than a bout of patent litigation ...

This Kat notices that the composition of the Court of Appeal again yokes together two specialist intellectual property judges (Lords Justices Floyd and Lewison) in the panel of three (the other member of the court being Lord Justice Longmore), and that both made substantive contributions to the published decision [the same phenomenon occurred in Fage v Chobani where the same three judges, on the same day, rendered a passing-off appeal]. He wonders whether this more collegiate approach will have a substantial impact on the quality of intellectual property decisions in the Court of Appeal, where we have so frequently been accustomed to the sole IP expert delivering a single judgment with which the other judges concur.The rule on added matter is that “...a patent application or patent may not be amended in such a way that it contains subject matter which extends beyond the content of the application as filed. If it has been so amended, and the added matter is not or cannot be removed, the patent will be invalid.” This neat description comes at the beginning of the decision of the Court of Appeal for England and Wales in AP Racing Ltd v Alcon Components [2014] EWCA Civ 40, a nuanced decision overturning the first instance order to revoke AP Racing's patent GB 2 451 690. Specifically, the court deals with the relationship in such cases between the breadth of a granted claim, and what is disclosed in both the specification of the granted patent and its corresponding application.

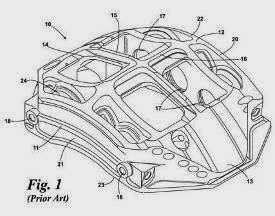

In essence, the patent application and granted patent in question are for disk brake calipers used in motor vehicles, and particularly the asymmetrical peripheral stiffening bands (“PSBs”) associated with the caliper body – embodied in the application as having a “J” or hockey stick shape.

The granted patent contained materially the same disclosure as the application, but dispute focused on whether the following feature of claim 1 of the granted patent was disclosed in the application:“in which each of the stiffening bands has a profile that is asymmetric about a lateral axis of the body when viewed in plan.”Two particular points arose in argument:

1. Is there a clear and ambiguous disclosure in the application of PSBs asymmetric about the lateral axis of the caliper body?

On this, the Court of Appeal held that, although not expressly stated in the application, it would be abundantly clear to the skilled reader that the PSBs were, individually, asymmetric about a lateral axis of the caliper body, and that the presence of the PSBs had the effect of giving the overall shape of the caliper body an asymmetric appearance.

2. Nonetheless, if only a class of generally hockey stick shaped PSBs is disclosed in the application, does the claimed feature contain added matter?

Answering this, the Court of Appeal said, depends on whether it is legitimate to add features to a claim which describe the invention in more general terms than a specific embodiment. Summarising authorities from the British courts and the Technical Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office, the Court of Appeal concluded that it was clear that the law “does not prohibit the addition of claim features which state in more general terms that which is described in the specification.”

In this case, the application would be understood by the skilled person as disclosing that the asymmetrical design of the PSBs was significant in imparting stiffness to the caliper, and that the hockey stick-shaped PSBs were “necessarily asymmetrical”. It must then be asked whether any disclosure has been added to this in the granted specification. The description of the PSBs in claim 1 as “asymmetric” must be read as part of that disclosure. From this, the skilled person would understand that the claim covered asymmetric PSBs generally. The skilled person would also understand that the PSBs were exemplified by the hockey stick shapes described in the specific embodiments. The skilled person would not, therefore, learn any new information about the invention from the granted patent.

In summary, what the Court of Appeal seems to be saying is that the skilled person would understand the breadth of the claim in question to be supported by a co-extensively broad disclosure in the application. Although the Court of Appeal never suggests this analysis, the case invites comparison with sufficiency cases in which the principle of an inventive concept derived from the specification can have a general application across a claim.

Merpel, who has been admiring Louis Wain's "Hockey", above, was a little anxious that all those cats might be hurting themselves and each other when playing so rough a sport. Then it occurred to her that even a bruising game of hockey might turn out less painful than a bout of patent litigation ...