He Contained Multitudes

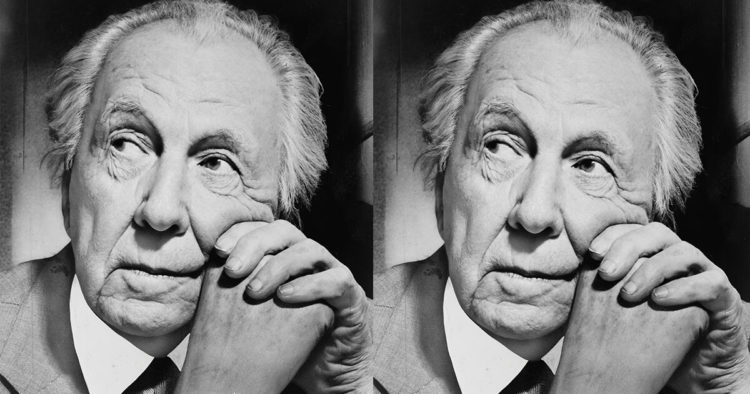

Wright in 1954 (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1957, while in New York supervising the construction of the Guggenheim Museum, Frank Lloyd Wright agreed to be interviewed on television by journalist Mike Wallace. By this time, Wright was 90 years old, the author of several hundred buildings, and a global celebrity—one who played the role of the uncompromising artist to the hilt.

About 10 minutes in, Wallace noted that a younger Wright had proclaimed that he would be the greatest architect of the 20th century. Had he reached his goal?

Wright denied that he had ever said such a thing. Wallace pointed out he had said it on the record, multiple times. Outflanked (for once), Wright partially backed down. “You know, I may not have said it, but I may have felt it,” he told Wallace. “But it’s so unbecoming to say it that I should have been careful about it. I’m not as couth as I’m generally reported to be.”

Not as couth: was this a calculated note of false modesty, laid on to charm (as was Wright’s habit), or was it something closer to candor? In his new book, Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright, Paul Hendrickson pushes back against the idea that Wright’s famous arrogance crowded out all feelings of shame, regret, humility, or sadness. Behind the superstructure of his ego, vulnerability was always “ghosting at the edges,” Hendrickson writes.

Yes, Wright peacocked around Chicago, and later Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Scottsdale, Arizona, in dandyish bespoke clothes, leaving unpaid creditors in his wake. He busted up two families (one of them his own) by running off with a married client, Mamah Borthwick Cheney. He had a bitter break from his mentor, Louis Sullivan, wheedled money out of friends and patrons, and told constant fabrications. Hendrickson doesn’t deny any of this. But he avers that Wright possessed a “fundamental decency,” and that he was haunted by the gothic personal tragedies that unfolded throughout his life, yet he seemed to endure them—and push through them to new artistic heights—with an uncanny resilience.

Taliesin, Wright’s 800-acre Wisconsin home, studio, and school. In 1914, it was the scene of a massacre. (Wikimedia Commons)

Plagued by Fire is not a standard biography; it moves back and forth, although in a broad chronological arc, exploring what its author calls “pockets” of incident in the architect’s life. The crux is the horrific crime that took place at Wright’s Wisconsin home and studio, Taliesin, in 1914, when a servant named Julian Carlton, in a sudden frenzy, murdered Cheney, her two young children who were visiting, and members of Wright’s staff, before setting the place ablaze. It would not be the last time that Taliesin would burn.

Hendrickson tracks what he calls the “chains of moral consequences” originating from this terrible event. Having scoured archives from Chicago to Alabama to Oklahoma, he contends that Carlton’s crime indirectly helped spark the Tulsa race riots of 1921—the unlikely vector being Wright’s cousin Richard Lloyd Jones, who edited a Tulsa newspaper. I won’t give away any more, but I found the theory plausible and the detective work dazzling. (Hendrickson makes his own research process a large part of the narrative; this works better when he is, for example, descending into the jail cell where Carlton was held than when he is enumerating the volumes in the Chicago phone directory for a given year.)

Yet as ingenious as this is, and as evocative of the moral calculus we all do when we look back at our mistakes: does it merit 50 or so pages in a book about Wright? A favorite method of Hendrickson’s is to lay out clues suggesting a hidden strand of Wright’s psychology, or a Faulknerian weight carried down the generations, and then quickly back away from the table: It’s just a theory. The truth is unknowable. But even so …

What this tells us about Wright the man is debatable; what it tells us about Wright the architect is not much. Readers interested in Wright’s work in the context of 20th-century architecture should consult a different biography (there are plenty). The author does include set-piece descriptions of several of Wright’s buildings; these are well observed and vividly described, although his prose can be cloying. “She’s so airy and light. She’s so mitered and mortared and tight. She’s so functional and spare and exquisitely livable,” Hendrickson writes of the Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin, the first of Wright’s scaled-down Usonian houses. The gendering of the house here is a tell. As psychobiography, this is Bloomian, anxiety-of-influence stuff, more interested in the men in Wright’s life than in the formidable women. Wright’s second wife, Maude Miriam Hicks Noel, is referred to throughout as “Mad Miriam”; his third wife, Olgivanna, has a fairly small role, despite having been married to Wright for three decades and having exerted a considerable influence on him.

At its best, Plagued by Fire has moments of raw emotional power. Who wouldn’t feel sympathetic for Wright after the massacre at Taliesin, as he made his way, in a state of shock, from Chicago to survey the ashes of the house he’d built and bury the woman he loved? Hendrickson takes us on an excruciating tour through those first hours and days, when Wright broke out in boils and played the piano through his sobs. But this gets at a larger question—and the underlying problem with the book. Does his humanity need to be proven? Or, to put it another way, surely no one today believes that Frank Lloyd Wright was a monster. Who doesn’t realize that pride and regret, conviction and weakness can coexist in the same person?

As I write this, eight of Wright’s buildings have just been added to UNESCO’s World Heritage List, the first works of modern American architecture that the UN agency has deemed “of outstanding universal value.” If you want to be convinced of Frank Lloyd Wright’s essential humanity, there’s a better way: just visit one of those buildings.

Permission required for reprinting, reproducing, or other uses.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2OaFeP0