VPN⁰: A Privacy-Preserving Distributed Virtual Private Network

This research presents VPN⁰, the first distributed virtual private network offering a privacy preserving traffic authorization and validation mechanism.

This research was conducted by Dr. Matteo Varvello (Performance Researcher at Brave), Iñigo Querejeta-Azurmendi (intern at Brave), Dr. Panagiotis Papadopoulos (Security Researcher at Brave), Gonçalo Pestana (Research Engineer at Brave) and Dr. Ben Livshits (Brave’s Chief Scientist).

Distributed virtual private networks (dVPNs) are a new form of VPN with no central authority. In a dVPN, users are both VPN clients and relay/exit nodes as in a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) network. While dVPNs make strong privacy claims, they also carry the risk that a user will inadvertently have their machine used to transmit potentially harmful or illegal network traffic. Several incidents have been reported [2] where unaware dVPN users have been (ab)used as exit nodes.

In our prior blog post, we analyzed several dVPN proposals and reported a lack of (i) performance, (ii) privacy guarantees, (iii) traffic accountability. In this post, we tackle these issues by introducing VPN⁰, to the best of our knowledge the first distributed virtual private network offering a privacy preserving traffic authorization and validation system.

VPN⁰ is founded on the idea that dVPN nodes should be able to decide which traffic they want to carry. For example, a dVPN node may only be willing to transmit network traffic related to news websites. To guarantee user privacy, this property should be achieved without learning the contents of the traffic a VPN user is transmitting. VPN⁰ presents a novel method for simultaneously achieving both of these goals.

We have integrated VPN⁰ with BitTorrent’s DHT (Mainline) and ProtonVPN, a popular VPN provider. We demonstrate the feasibility of VPN⁰ and also benchmark its performance with respect to DHT lookup, VPN tunnel setup, and zero-knowledge traffic attestation.

VPN⁰ Design

VPN⁰ allows relay nodes to control which traffic they transmit, without learning what content it contains, through a novel application of zero knowledge proofs. A zero knowledge proof is a cryptographic technique that allows a prover to prove to a verifier that a certain statement is true, without disclosing any information except the validity of the statement. In our case, a VPN⁰ client wants to prove to a VPN⁰ relay that the traffic it is sending is contained within the relay’s whitelist, or a set of domains the relay is willing to carry traffic for.

Several challenges exist to realize this goal in a decentralized system. In the following, we present each challenge along with a high level description of the solution we have devised. The interested reader can find a complete and more technical description of each solution in our article.

Challenge 1: Private Whitelist Sharing

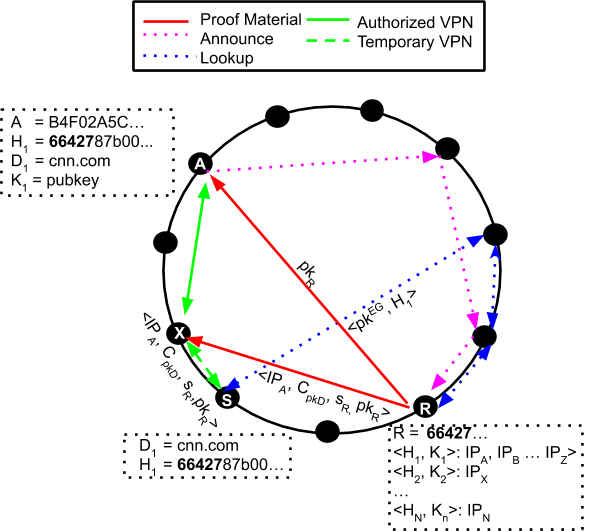

Figure 1: Flow of a connection using VPN-zero. First, nodes announce their whitelists. Then, when a user wants to connect to a domain, it first uses a temporary VPN, and then performs a lookup to find the node to create an authorized VPN with.

VPN⁰ leverages a Distributed Hash Table (DHT) — a class of distributed systems that provides a lookup service similar to a hash table — to privately locate at least a VPN⁰ node willing to act as VPN relay node for some specific traffic. To this end, VPN⁰ nodes announce in the DHT each entry of their whitelists using the hash of the domain name as a key, and as a value the domain's public key and their current public IP address. VPN⁰ clients leverage the DHT to privately lookup VPN⁰ nodes willing to serve their content. Figure 1 shows an example ofboth announce (magenta dashed line) and lookup (blue dashed line) operations.

Challenge 2: Zero-Knowledge Traffic Proof

A VPN⁰ client is required to prove to a VPN⁰ relay that the traffic it is sending is contained within the node's whitelist, in zero knowledge. This is achieved by piggybacking on TLS to build a proof of visit. Precisely, on the information derived from the encryption of the Server Name Indication (SNI) field in the ClientHello (as discussed in this RFC draft related to TLS v1.3). While VPN⁰ can be extended to work with regular TLS v1.3 as well as v1.2, the less private nature of such traffic would allow snoopy relay nodes to potentially violate the privacy of a VPN⁰ client.

After the DHT lookup, a VPN⁰ client receives the relay's IP willing to take the corresponding traffic and an encryption of the accessed service provider's public key — the one present in the certificate of the website the client is accessing. Combining this encrypted public key with the encrypted SNI gives enough tools to the VPN⁰ client to prove that the service being accessed corresponds, with high probability, to a service announced as authorized during the private whitelist sharing phase.

In order to produce this proof, the TLS v1.3 handshake together with the RFC extension discussed above must happen through the relay. If the proof presented by the VPN⁰ client verifies correctly, and the TLS handshake succeeds, the relay is convinced that the server for which it is acting as a relay is, with a high probability, among its whitelisted services; this probability captures the prevalence of honest nodes in the system. A potential avenue of attack here is a collusion between the relay and the DHT node(s) responsible for announce/lookup operations for a domain. This translates into a sybil attack, a popular attack on the DHT for which many countermeasures exist [7].

Challenge 3: Balancing Performance and Strict Privacy Guarantees

VPN⁰ aims to offer strict privacy guarantees with no performance penalty for its users. We achieve so by introducing VPN chains. When a VPN⁰ client wants to visit a domain, it first opens a classic VPN connection to any VPN⁰ node. In the background, VPN⁰ software privately locates a second node which is willing to carry this specific traffic, and forward all the cryptographic material required (see Figure 1 and our article for a detailed description of the protocol execution). When found, the temporary VPN relay transparently chains the first VPN tunnel with a new VPN tunnel towards the designated exit node, with no noticeable impact at the user.

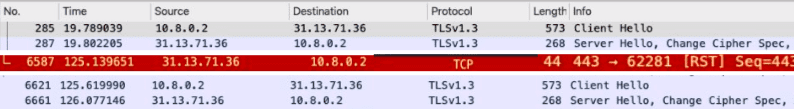

Figure 2: TCP and TLS connection (re)negotiation triggered by a VPN⁰ chain.

The latter operation has two main effects. First, it provides continuation of VPN service while the privacy preserving protocol is executed. Second, it allows the actual VPN⁰ exit node to verify, in zero knowledge, that the ongoing traffic is allowed. This is possible because the remote website will notice a change in the underlying TCP connection, i.e., a new socket endpoint and wrong TCP sequence number, causing a TCP RST — see in Figure 2 the wireshark log of a TCP RST triggered when accessing Facebook through VPN⁰. This will travel back to the VPN⁰ client forcing a new TCP handshake and thus TLS handshake. This new TLS handshake can now be observed by the final exit node. The SNI encryption in the new ClientHello is used to verify (in zero knowledge) that the destination domain is within its whitelist.

Evaluation

To make sure VPN⁰’s design can support real world use, we integrated it with Mainline (BitTorrent DHT with tens of millions of users), and ProtonVPN (a popular VPN provider). We further use OpenVPN to run the first VPN path on a Raspberry Pi under our control.

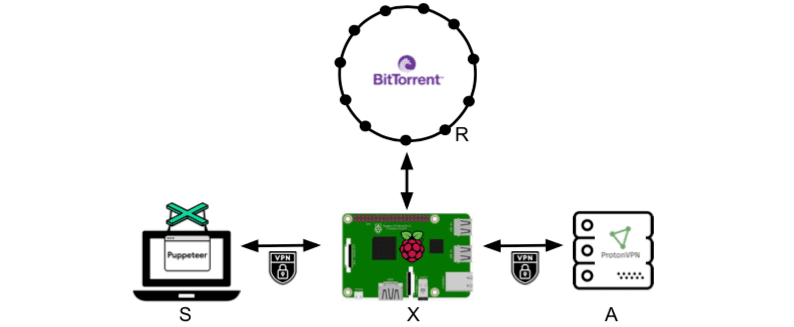

Figure 3: High level overview of VPN⁰’s prototype.

Figure 3 shows a graphical representation of our testbed. A headless browser runs on a laptop (node S) and it is instrumented to visit a TLSv1.3-enabled website. The laptop connection is tunneled through a Raspberry Pi (node X) located in the same LAN as S; note that this is a worst case scenario for VPN⁰ since the extra network latency would further hide the latency of the traffic verification process.

Whenever a new website visit is initiated, node X performs a DHT query in Mainline. As input for the DHT query, we use one of the top 100 magnet links (DHT hashes) as indicated by a popular indexing website for BitTorrent content. As soon as the DHT response is received, X opens a new tunnel to a random ProtonVPN server (node A) from the list provided with a basic subscription, and proceeds with setting up the VPN chain. Meanwhile, the ZKP is calculated at S to be then sent to A where the ZKP can be verified.

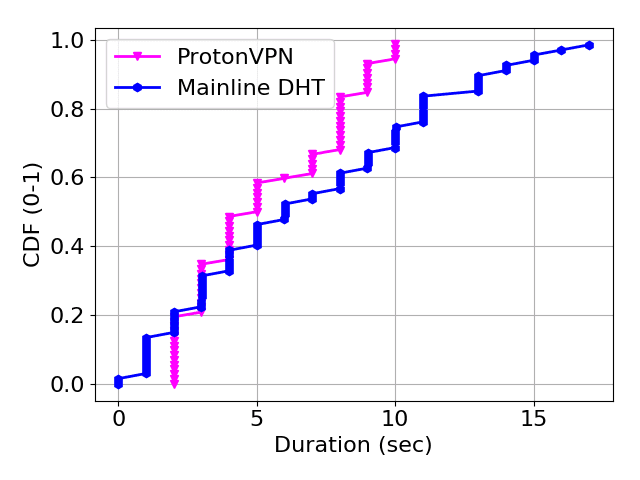

Figure 4 shows the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) of DHT lookup duration in the Mainline DHT for the 100 hashes under tests. Overall, we observe a uniform distribution between 1 and 20 seconds. Contributions to this delay are: diverse network paths taken by DHT lookups, failures along the path, lookup replication factor, etc.

Figure 4: CDF of DHT loop duration and VPN setup time.

The next operation, post DHT lookup, is the setup of the second leg of the VPN chain. The figure also shows the CDF of such VPN setup time computed for 72 VPN nodes — 96 nodes were tested but 24 failed, i.e., negotiation did not succeed within 30 seconds. This high failure rate is potentially due to a ProtonVPN protection for too frequent switches. The figure shows a median reconnect time of 4 seconds and worst case durations of up to 10 seconds.

Finally, we benchmarked our ZKP calculation using a Python prototype implementation and measured an average of 10 seconds. This time is overall slower than both VPN chain setup and DHT lookup, and thus the current bottleneck of VPN⁰. It has to be noted that, from a user perspective, the setup time of VPN⁰ is as fast as a classic VPNs, e.g., in our demonstration as fast as ProtonVPN. This is because our design purposely hides the extra operations required, i.e., DHT lookup, VPN chain setup, and ZKP calculation The drawback is that, during this time, potentially unauthorized traffic can flow through VPN⁰.

From this analysis, our main future work consists in minimizing the duration of potential unauthorized traffic. We plan to achieve this via both protocol improvements (e.g., optimized DHT lookup and chain selection) and by switching to better performing languages (Rust, C++) for the ZKP calculation. We also plan to perform more comprehensive measurements under realistic VPN workloads.

Conclusions

Decentralized VPNs (dVPNs) are VPN solutions where users share their resources in exchange for other users bandwidth or, more recently, a cryptocurrency compensation [3][4][5][6]. In our prior blog post, we noted that existing dVPN designs fail to provide strong privacy guarantees. Most notably, their decentralized nature requires strong guarantees on the traffic a dVPN node carries without violating a user's privacy, at any time.

This post has presented VPN⁰, to the best of our knowledge, the first dVPN with strong privacy requirements and high performance. VPN⁰ is built around a Distributed Hash Table (DHT) atop of which we designed several privacy preserving mechanisms. Most notably, a strategy to prove, in zero knowledge, that a dVPN client is attempting to access a TLS domain. This information is used by dVPN nodes to only allow through them traffic they are willing to carry, without violating dVPN users’ privacy.

We integrated VPN⁰ with BitTorrent DHT and ProtonVPN, and benchmarked its performance. Our preliminary results show the feasibility of the approach but they also highlight a need for more research to speed up VPN⁰’s zero knowledge calculations. We believe the strong privacy guarantees offered by VPN⁰ will foster the development of future VPN solutions and protocols.

We foresee the ideas contained here to be the foundation of a decentralized VPN system, which may be combined with a set of incentives around a utility token such as BAT (Basic Attention Token). In a scenario like this, users carrying traffic would be compensated in BAT and users would pay for VPN services or subscriptions in BAT, as well. Care must be taken to make sure that token economic incentives keep this model continuously attractive for all participants and also that BAT payments cannot be used to deanonymize the participants.

References

[1] Khan, M.T., DeBlasio, J., Voelker, G.M., Snoeren, A.C., Kanich, C. and Vallina-Rodriguez, N., 2018, October. An empirical analysis of the commercial vpn ecosystem. In Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference 2018(pp. 443-456). ACM.

[2] http://adios-hola.org/ (if unavailable, check https://web.archive.org/web/20190510183022/http://adios-hola.org/)

[3] Sentinel.co. Sentinel: Interoperable Network Layer for Distributed Resources. https://sentinel.co/.

[4] The Mysterium Network. Mysterium Network: Decentralised VPN Built on Blockchain. https://mysterium.network/.

[5] Privatix Network. Get Paid for Unused Internet. https://privatix.io/

[6] Lethean. VPN and Wallets. https://lethean.io/vpn-and-wallets

[7] T. Cholez, I. Chrisment, and O. Festor. Evaluation of sybil attacks protection schemes in kad. In IFIP International Conference on Autonomous Infrastructure, Management and Security, pages 70–82. Springer, 2009.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2ppBTBb