Why iOS 13 and Catalina Are So Buggy

iOS 13 and macOS 10.15 Catalina have been unusually buggy releases for Apple. The betas started out buggy at WWDC in June, which is not unexpected, but even after Apple removed some features from the final releases in September, more problems have forced the company to publish quick updates. Why? Based on my 18 years of experience working as an Apple software engineer, I have a few ideas.

Overloaded Feature Lists Lead to Schedule Chicken

Apple is aggressive about including significant features in upcoming products. Tight schedules and ambitious feature sets mean software engineers and quality assurance (QA) engineers routinely work nights and weekends as deadlines approach. Inevitably some features are postponed for a future release, as we saw with iCloud Drive Folder Sharing.

In a well-run project, features that are lagging behind are cut early, so engineers can devote their time to polishing the features that will actually ship. But sometimes managers play “schedule chicken” since no one wants to admit in the departmental meeting that their part of the project is behind. Instead, they hope someone else working on another aspect of that feature is running even later, so they reap the benefit of the feature being delayed without taking the hit of being the one who delayed it. But if no one blinks, engineers continue to work on a feature that can’t possibly be completed in time and that eventually gets pushed off to a future release.

Apple could address this scheduling problem by not packing so many features into each release, but that’s just not the company culture. Products that aren’t on a set release schedule, like the AirPods or the rumored Bluetooth tracking tiles, can be delayed until they’re really solid. But products on an annual release schedule, like iPhones and operating systems, must ship in September, whatever state they’re in.

Crash Reports Don’t Identify Non-Crashing Bugs

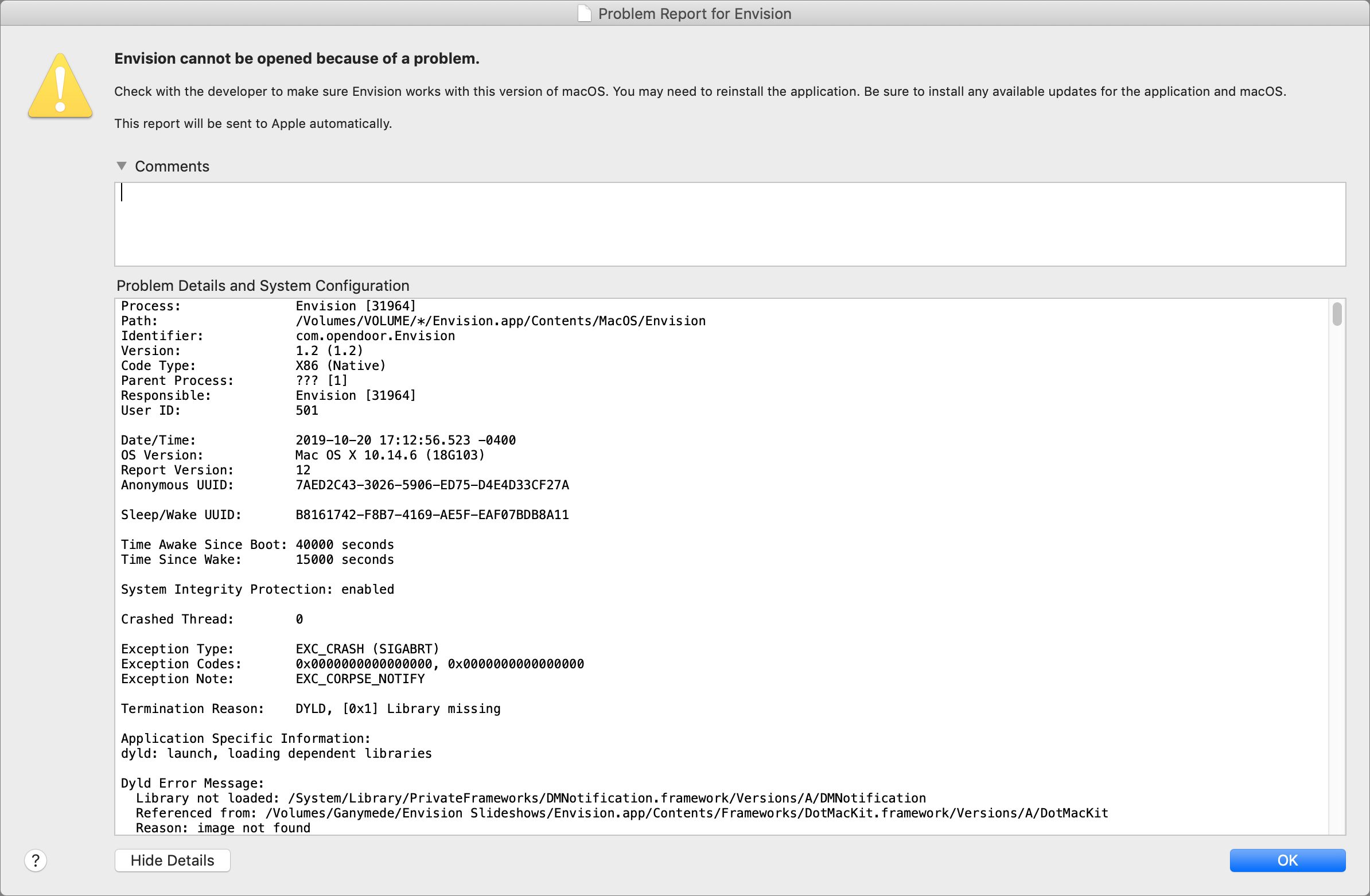

If you have reporting turned on (which I recommend), Apple’s built-in crash reporter automatically reports application crashes, and even kernel crashes, back to the company. A crash report includes a lot of data. Especially useful is the stack trace, which shows exactly where the code crashed, and more importantly, how it got to that point. A stack trace often enables an engineer to track down the crash and fix it.

Crash reports are uniquely identified by the stack trace. The same stack trace on multiple crash reports means all those users are seeing the same crash. The crash reporter backend sorts crash reports by matching the stack traces, and those that occur most often get the highest priority. Apple takes crash reports seriously and tries hard to fix them. As a result, Apple software crashes a lot less than it used to.

Unfortunately, the crash reporter can’t catch non-crashing bugs. It’s blind to the photos that never upload to iCloud, the contact card that just won’t sync from my Mac to my iPhone, the Time Capsule backups that get corrupted and have to be restarted every few months, and the setup app on my new iPhone 11 that got caught in a loop repeatedly asking me to sign in to my iCloud account, until I had to call Apple support. (These are all real problems I’ve experienced.)

Apple tracks non-crashing bugs the old-fashioned way: with human testers (QA engineers), automated tests, and reports from third-party developers and Apple support. Needless to say, this approach is as much an art as it is a science, and it’s much harder both to identify non-crashing bugs (particularly from reports from Apple support) and for the engineers to track them down.

Less-Important Bugs Are Triaged

During development, Apple triages bugs based on the phase of the development cycle and the bug severity. Before alpha, engineers can fix pretty much any bug they want to. But as development moves into alpha, and then beta, only serious bugs that block major features are fixed, and as the ship date nears, only bugs that cause data loss or crashes get fixed.

This approach is sensible. As an engineer, every time you change the code, there’s a chance you’ll introduce a new bug. Changes also trigger a whole new round of testing. When you’re close to shipping, a known bug with understood impact is better than adding a fix that might break something new that you’d be unaware of.

Bugs that generate a lot of Apple Store visits or support calls usually get fixed. After all, it costs serious money to pay enough support reps to help lots of users. It’s much cheaper to fix the bug. When I worked on Apple products, we’d get a list of the top bugs driving Apple Store visits and support calls, and we were expected to fix them.

Unfortunately, bugs that are rare or not terribly serious—those that cause mere confusion instead of data loss—are continually pushed to the back burner by the triage system.

Regressions Get Fixed. Old Bugs Get Ignored.

Apple is lousy at fixing old bugs.

Apple pays special attention to new products like the iPhone 11, looking for serious customer problems. It jumps on them quickly and generally does a good job of eradicating major issues. But any bugs that are minor or unusual enough to survive this early scrutiny may persist forever.

Remember what I said about changes causing new bugs? If an engineer accidentally breaks a working feature, that’s called a regression. They’re expected to fix it.

But if you file a bug report, and the QA engineer determines that bug also exists in previous releases of the software, it’s marked “not a regression.” By definition, it’s not a new bug, it’s an old bug. Chances are, no one will ever be assigned to fix it.

Not all groups at Apple work this way, but many do. It drove me crazy. One group I knew at Apple even made “Not a Regression” T-shirts. If a bug isn’t a regression, they don’t have to fix it. That’s why the iCloud photo upload bug and the contact syncing bug I mentioned above may never be fixed.

Automated Tests Are Used Sparingly

The software industry goes through fads, just like the fashion industry. Automated testing is currently fashionable. There are various types of automated testing: test-driven design, unit tests, user-driven testing, etc. No need to go into the details here, except to say that, apart from a few specific areas, Apple doesn’t do a lot of automated testing. Apple is highly reliant on manual testing, probably too much so.

The most significant area of automated testing is battery performance. Every day’s operating system build is loaded onto devices (iPhones, iPads, Apple Watches, etc.) that run through a set of automated tests to ensure that battery performance hasn’t degraded. (Of course, these automated tests look only at Apple code, so real-world interactions can—and often do—result in significant battery performance issues that have to be tracked down and fixed manually.)

Beyond batteries, a few groups inside Apple are known for their use of automated tests. Safari is probably the most famous. Every code check-in triggers a performance test. If the check-in slows Safari performance, it’s rejected. More automated testing would probably help Apple’s software quality.

Complexity Has Ballooned

Another complication for Apple is the continually growing complexity of its ecosystem. Years ago, Apple sold only Macs. Processors had only one core. A program with 100,000 lines of code was large, and most were single-threaded.

A modern Apple operating system has tens of millions of lines of code. Your Mac, iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, AirPods, and HomePod all talk to each other and talk to iCloud. All apps are multi-threaded and communicate with one another over the (imperfect) Internet.

Today’s Apple products are vastly more complex than in the past, which makes development and testing harder. The test matrix doesn’t just have more rows (for features and OS versions), it also has more dimensions (for compatible products it has to test against). Worse, asynchronous events like multiple threads running on multiple cores, push notifications, and network latency mean it’s practically impossible to create a comprehensive test suite.

Looking Forward

In an unprecedented move, Apple announced iOS 13.1 before iOS 13.0 shipped, a rare admission of how serious the software quality problem is. Apple has immense resources, and the company’s engineers will tame this year’s problem.

In the short term, you can expect more bug fix updates on a more frequent schedule than in past years. Longer-term, I’m sure that the higher-ups at Apple are fully aware of the problem and are pondering how best to address it. Besides the fact that bugs are expensive, both in support costs and engineer time, they’re starting to become a public relations concern. Apple charges premium prices for premium products, and lapses in software quality stand to hurt the company’s reputation.

David Shayer was an Apple software engineer for 18 years. He worked on the iPod, the Apple Watch, and Apple’s bug-tracking system Radar, among other projects.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2BvX7Ae