Australian solar farm has to switch off every second day due to negative prices

When Australia’s renewable energy portfolio reached its important milestone on Wednesday of providing 50 per cent of the main grid’s demand for the first time, one solar farm couldn’t be part of the fun, and had to look on from the sidelines.

The sight of wind and solar farms being switched off when wholesale electricity prices fall into negative territory has become increasingly common over the last few months, particularly in Queensland and South Australia.

But the facility that appears to have been affected the most has been the 95MW Tailem Bend solar farm in South Australia, owned by Vena Energy and operating since earlier this year.

Tailem Bend has an off-take agreement with Snowy Hydro that requires it to switch off when wholesale electricity prices go into negative territory.

And Tailem Bend just so happens to be located in the state – South Australia – which already operates at more than 50 per renewables on a yearly average, and is often at more than 100 per cent, and so has the greatest propensity to experience negative prices.

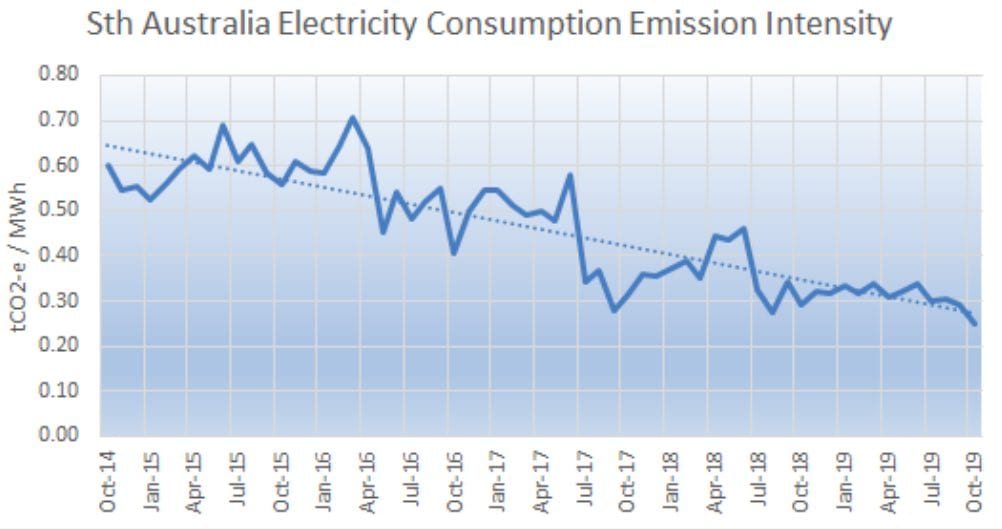

Indeed, its average price for the month of October was lower than any other state in the main grid, including those dominated by coal. A month, incidentally, when the state’s grid emissions also fell, continuing the major reduction in emissions achieved over the last five years as coal was replaced by wind and solar.

But back to Tailem Bend. Over the last two months, negative prices have been occurring so often (due to low demand, good wind conditions and sunny skies) that this solar plant has been obliged to switch off on virtually ever second day – on 14 different days in September and 18 days in October.

It’s common to see wind and solar farms switch off when prices go into negative territory, or get close to zero. It happens either because their off-take agreements oblige them to do so, or because they are “merchant” facilities that take the spot price and don’t want to be paying other parties to take their output if prices do go negative.

It should be noted that this is pretty standard fare for all generators, be they wind, solar, gas or coal. You won’t see many peaking gas stations switched on at less than $100/MWh, and likely much higher.

Some peaking gas plants operate just two per cent of the time. Some diesel plants, built under capacity payments, don’t switch on at all, because they are not needed, and if they did switch on they would lose money because they prices they would receive would not cover the cost of the diesel fuel.

In the days when coal reigned supreme, many plants had to switch off or ramp down at times of low demand, which then happened mostly at night (as opposed to during the day now, because of the impact of rooftop solar).

Those coal plants that couldn’t or wouldn’t switch off were given something to do, so electric hot water systems were switched on only at night, and low tariffs offered to businesses to make things overnight. Now that solar is changing the demand curve, manufacturing and hot water systems are now looking to move back to day-time hours.

Still, the idea behind the low cost of wind and solar is that the relatively high capital costs of the facilities are more than made up by the negligible cost of generation (no fuel to pay for, because the sun and the wind come free). That business model usually dictates that they should operate whenever possible.

Most wind and solar farms can expect some level of constraints – because of weather situations, levels of demand, network issues and other stuff that is going on in the grid, and that’s part and parcel of how the electricity system operates – but it’s hard to imagine that a solar farm expected to be switched off this often.

This graph above, provided by Global Roam, the authors of NEM Review providers of the popular NEM-Watch widget that can be found on RenewEconomy, shows examples of recent weeks when Tailem Bend was forced to switch off virtually every day.

The orange represents when the solar plant is generating, and how much. Look for the gaps in the orange and the thin brown line, and the white below that line. That indicates the solar plant was “available” but not generating. That’s not because of passing clouds, but because prices went negative (the green line).

Vena would not comment, because they said the terms of the off-take agreement were commercial-in-confidence (In Australia, parties to such deals won’t even reveal the price, let alone other conditions), but it did indicate that negative pricing events were not unexpected, and had been dialled into its business model.

Negative pricing events have been occurring regularly in Queensland as well, including on one day in early September when much of the state’s 20 plus fleet of solar farms switched off en masse, either because they were obliged to do so or because they didn’t want to take a hit from negative prices.

The creation of CleanCo may help change that situation, because it will now be inclined to deploy the previously little used 570MW Wivenhoe pumped storage facility, which acts like a giant battery, to charge during those low prices during the day, rather than during the night when it would help out the coal generator operator by its previous owner.

That might be enough to drag the prices out of negative territory on most occasions. Time will tell.

South Australian wind and solar farms will have to wait a little longer. It now has three batteries that can charge at low prices – Hornsdale, Dalrymple North, and now Lake Bonney – but these installations are still relatively small and are mostly busy doing other things, either on standby for emergency response or playing in the frequency and ancillary services market.

The new battery at Lake Bonney will do some FCAS, and may take some excess from the merchant component of Infigen Energy’s neighbouring 275MW wind facility of the same name, but it wouldn’t take long to fill.

Salvation, or less frequent negative pricing events, likely won’t come until the new interconnector to NSW is built, maybe by late 2023, and/or one of the first pumped hydro facilities in the state also come on line. A decision on funding the first of those projects is expected soon.

Meanwhile, just about every new large scale wind and solar project proposal, or wind and solar hybrid, is now coming with storage attached, and there are a growing list of huge projects that will likely propel the state towards its unofficial target of “net 100 per cent renewables” by around 2030, such as this solar and storage project contracted by Alinta.

Tailem Bend is also considering a battery storage, but the Vena people would not comment on where they were with that idea. Safe to assume, perhaps, that if the proposed second stage of Tailem Bend goes ahead, batteries will be included.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2JWddaY