How to Kickstart and Scale a Marketplace

“Everyone's always looking for the hack - what's the channel that will unlock something big? But every time we looked for a reason we weren't growing, it always came back to the basics –– selection, delivery quality, pricing. That's it. Always come back to first principles. Whenever we made a mistake, we forgot this.”

– Micah Moreau (DoorDash, VP of Growth)

(This is a special edition of my newsletter — the first in a series of posts sharing insights from interviews with founders and early employees at today’s most successful marketplace businesses. Our regularly scheduled weekly Q&A series will resume in a few weeks.)

Having worked at Airbnb for many years, I’m frequently asked about what Airbnb did right in order to grow into what it is today. While sharing my learnings, I’ve become increasingly wary of teams relying too heavily on a single company’s experience. There are so many factors that go into an eventual success story, and what’s effective once may not be again. Thus, I’ve been yearning to get a wider perspective on what has (and hasn’t) worked for other marketplace companies.

Since I couldn’t find anything out there that was comprehensive enough, I decided to be the change I want to see in the world and do the primary research myself. Over the past few months, I’ve had the good fortune to interview dozens of incredible people with direct experience building and scaling some of the most successful marketplace companies in the world. I’ve consolidated their learnings into a sort-of-playbook to kickstart and grow a successful marketplace business — which I’ll be sharing as bite-sized posts over the next few weeks:

Phase 1: Crack the chicken-and-egg problem 🐣

Part 1: Constrain the marketplace 🔬 (this post)

Part 2: Decide which side of the marketplace to concentrate on 🧐

Part 3: Drive initial supply 🐥

Part 4: Drive initial demand 👋

Phase 2: Scale your marketplace 📈

Part 1: Determine if you are supply or demand constrained 🤹♂️

Part 2: Scale growth levers 🔥

Part 3: Maintain quality 🏅

Phase 3: Evolve your marketplace 🐛

This work would not have been possible without the enormous generosity of countless people, all willing to share their precious time, stories, and insights with me simply because I asked. The readiness to share so openly and transparently says a lot about the value people in the tech industry place on sharing and giving back. A very special thank you to Andrew Chen (ex-growth at Uber, GP at a16z), Babak Nivi (co-founder of AngelList), Benjamin Lauzier (ex-growth at Lyft, Director of Product at Thumbtack), Brian Rothenberg (ex-growth at Eventbrite and TaskRabbit, Partner at defy), Casey Winters (ex-growth at GrubHub, CPO at Eventbrite), Dan Hockenmaier (ex-growth at Thumbtack, founder of Basis One), Dan McKinley (ex-Etsy, Principal Engineer at MailChimp), David Rosenthal (ex-Rover, GP at Wave Capital), Georg Bauser (ex-Airbnb, CEO of Expansion Partners), Gilad Horev (VP Product at Eventbrite), Gokul Rajaram (Caviar Lead), Gustaf Alströmer (ex-growth at Airbnb, partner at YC), Hunter Walk (partner at Homebrew), Jamie Viggiano (ex-marketing at TaskRabbit, CMO at Fuel Capital), Julien Smith (co-founder of Breather), Kati Schmidt (ex-Airbnb), Max Mullen (co-founder Instacart), Micah Moreau (VP Growth at DoorDash), Mike Duboe (ex-growth at Stitch Fix, investor at Greylock), Mike Xenakis (ex-SVP of Product at OpenTable, Lecturer at Kellogg School of Management), Nickey Skarstad (ex-Director of Product at Etsy, VP of Product at The Wing), Nate Moch (VP at Zillow), Sander Daniels (co-founder of Thumbtack), Tal Raviv (growth at Patreon), and Tamara Mendelsohn (VP and GM at Eventbrite). Unless otherwise stated, all of the quotes below come from my direct interviews.

Background

What is a marketplace business, anyway?

A marketplace business is one that (1) connects demand (i.e. people who want a thing) with (2) supply (i.e. people who have that thing), and (3) leads to a financial transaction. These businesses do not generally own any supply, do not provide products or services directly, and (eventually) handle the money being exchanged. Simply put, their job is to provide a platform where the supply and demand efficiently find each other and transact successfully.

Examples of classic marketplace businesses: Airbnb, Uber, Lyft, Alibaba, eBay, Etsy, Hipcamp, DoorDash, Caviar, Rover, Postmates, Thumbtack, TaskRabbit, Craigslist

Examples of non-marketplace businesses: Delta Airlines (they own all of the inventory), YouTube (no financial transaction), Slack (no supply).

Why are marketplaces great businesses?

Network effects: The more users you get, the more useful/cheap your product becomes, the more users you get (e.g. Lyft/Uber vs. taxis)

Barrier to entry: Once they have a strong network effect, it becomes increasingly difficult to enter or replicate the marketplace (e.g. Airbnb vs. hotels)

Efficiency: No inventory means cheaper to operate (e.g. Airbnb vs. hotels)

Scalability: No inventory means easier to scale (e.g. Rover vs. dog hotels)

Flexibility: No inventory means easier to pivot (e.g. Uber Black -> Uber X)

Important disclaimers

For many of these companies, the primary reason they became successful was not because of some amazing growth insights – it was primarily because of great product/market fit. Many folks I spoke to are first to admit this. The growth levers they employed helped accelerate (and control) growth, but they may have been successful anyway. At least for a while.

Past behavior is not predictive of future behavior. When reading through the lessons below, my advice is to focus more on ways of thinking and the cleverness behind the ideas –– not only the specific tactics. Many of the most successful growth levers of the past no longer work, or are significantly less effective. Take inspiration from what you read, but don’t expect them to work the same way for you.

This research is based on interviews, of events many years ago. Memory can be faulty, takeaways could be anecdotal, and you often don’t really know what mattered in the end. Also, I probably got some stuff wrong, so please don’t take any of this as gospel (and I’ll include any corrections in future posts). All that being said, I’ve tried my best to triangulate what actually happened across multiple sources, and made sure things felt right.

With those caveats in mind, let’s dive in!

How to Build a Marketplace Business

Phase 1: Crack the chicken-and-egg problem 🐣

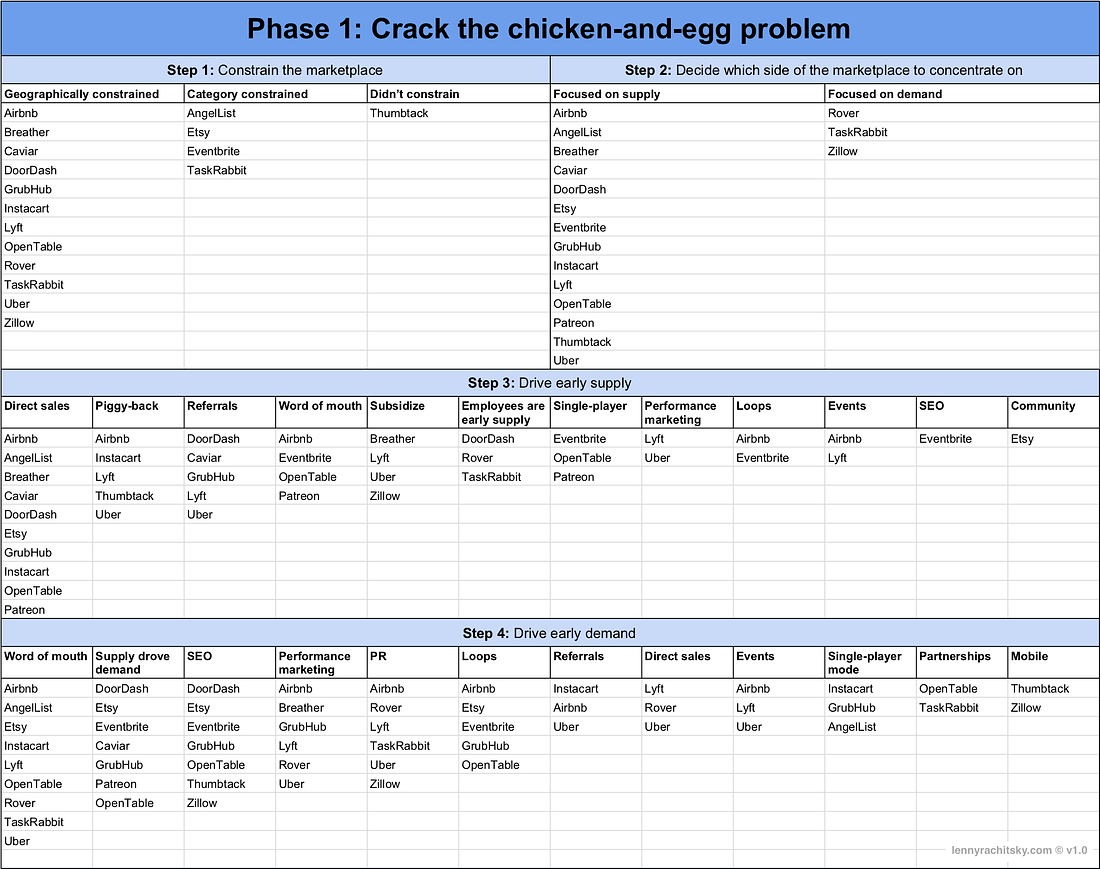

Once a marketplace business is operating, supply (i.e. restaurants, homes, drivers) happily serve demand (i.e. eaters, travelers, passengers). However, when your marketplace is just getting started, and you have neither supply nor demand, it’s challenging to get the flywheel going. You must convince once side of the marketplace to commit before the other side. For example, without restaurants onboard, a customer looking for food has no reason to check your app. And without customers using your app, restaurants have very little reason to spend time onboarding onto your platform. This is known as the “chicken-and-egg problem”, and solving it is one of the biggest barriers to launching a marketplace business. Below, and over the next few posts, we’ll walk through the steps that the biggest marketplaces worked through in order to crack this problem. Also, here’s a cheat sheet:

Step 1: Constrain the marketplace 🔬

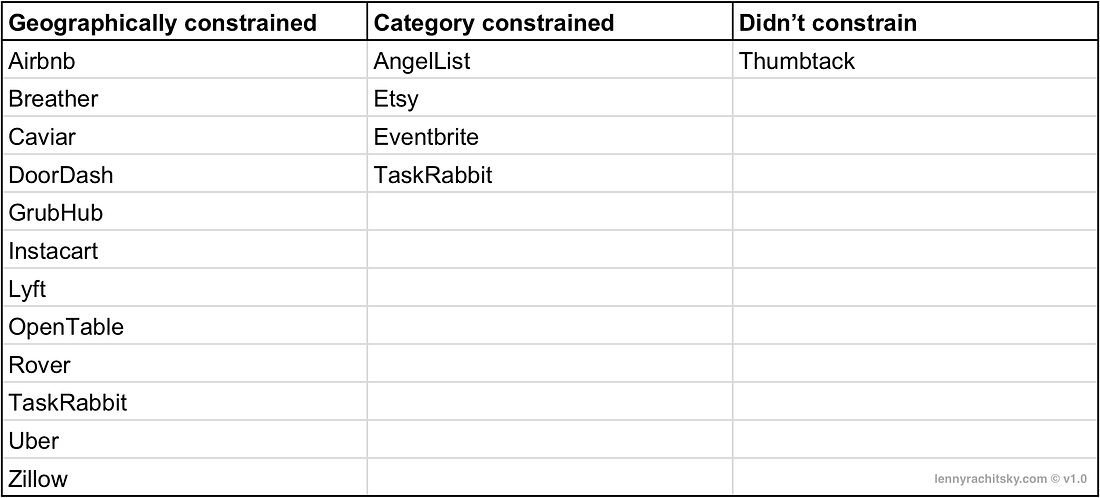

The first major learning that emerged from this research is that, with the exception of one company, every single marketplace that I interviewed constrained their initial marketplace to more quickly get to critical mass. To some this may seem counter-intuitive — why limit your growth and opportunities when you are starting out? It turns out that the best way to get big is by first going small.

The research points to two ways to constrain a marketplace: (1) geographically, and (2) by category. If the offering requires supply and demand to be in the same physical location, the constraint is always geographical (e.g. a limited set of markets). Otherwise, it’s category-based (e.g. handmade goods). And the one exception to this rule, Thumbtack, is a fascinating case study in and of itself.

If the service requires supply and demand to meet, it always started with a geographic constraint (i.e. a single market)

Rover:

“We started in Seattle, and stayed hyper-focused on Seattle, for a while. Seattle was the perfect market for us: very dog-friendly, early adopters, techy, working professionals who go on vacation and business trips. Plus Amazon is super dog-friendly. There is probably no more dog-friendly city in America. This helped figure out the product quickly.”

— David Rosenthal

Airbnb:

“Similar to how the founders first focused on New York early on, when Airbnb expanded internationally in 2011, we focused on creating critical mass in just a few markets in which we were quickly able to unlock supply and demand.”

— Kati Schmidt

Uber:

“We created a playbook for opening up a new market, which got set by the Launcher team (led by Austin Geidt). The first thing they would do when they launched market is to figure out supply. The goal was to get over 30 drivers, shooting for ETA of less than 15 minutes.”

— Andrew Chen

OpenTable:

“We ultimately discovered if we had enough restaurants in a market, we’d have enough value for the diner to use OpenTable. Dining is local, so concentration was key. A rule of thumb was that if we could get to 50-100 concentrated restaurants in a city, we had enough for a consumer to land on the site, cast a wide net, and get a consideration set that was meaningful enough to not be disappointed.”

— Mike Xenakis

Instacart:

“We selected our initial markets where there would likely be demand, e.g. Chicago in the winter. A high household income, fewer households with cars, and frequently inclement weather — typically means people want delivery.”

— Max Mullen

Breather:

“When transaction length was low (a 2 hour room booking), proximity was super important. We had areas of density like the Flatiron District, where we added units and they kept getting booked immediately. It was clear product/market fit. We followed this in a super dense and a very precise way. This cafe, at this location, at this time, is working. Duplicate this exactly. Don’t try to create something else. Don’t try to launch a new city yet. Don’t change anything. What is the exact same thing I can duplicate or extend? What else can this customer go do after? How can I double the size of the transaction. A lesson of marketplace companies -- if you are in a place with a decent market size, then just double down on what’s working. You don’t need to do anything new. Like with Airbnb, it was working in NY, so just create that again and again and again.”

— Julien Smith

Zillow:

“When we started the mortgage marketplace, there were no automated systems for anonymous, accurate, real time mortgage rates. So we had to start small in a single market and work with mortgage brokers who would respond to emails and manually enter quotes by hand every day.”

— Nate Moch

Essentially every other marketplace (not location-based) started with a category constraint:

TaskRabbit:

“While we were always a broad platform, we were very deliberate about building a liquid marketplace for our most popular task categories, which were and continue to be: handyman tasks (including IKEA assembly), house cleaning, and moving help. We focused on these categories to ensure that there was high-quality supply to meet the consumer demand for these services.”

— Jamie Viggiano

Eventbrite:

“Find your core use-case, and gain traction there. For Eventbrite, this was tech mixers and conferences. As you got invites from events, you started to see the name Eventbrite over and over and it became a thing. We focused on this, based on seeing where most early traction was.”

— Brian Rothenberg

Etsy:

“From the beginning, we had only three categories of things you could sell: vintage items, craft supplies, and handmade items.”

— Etsy, Dan McKinley

In one rare, fascinating, and deliberate case, Thumbtack decided to eschew any constraint:

“The conventional wisdom was to narrow focus to a category (like Amazon did with books) or geography (like Yelp did with San Francisco). We didn't get funding for many years in part because we did the opposite -- we did all categories and all geographies from the beginning. People thought that wouldn't work, that we were boiling the ocean. In retrospect it was the only way to build a marketplace in our space at scale -- being broad in category increased the frequency of use of our product from once every couple years (how often do you need to hire a house painter?) to 8-12 times a year (the number of Thumbtack services an average American household hires annually). And being broad in geography allowed us to scale our marketplace as fast as possible, giving us the revenue, traffic, and thus experimental velocity we needed to bootstrap a great product. In our case we wouldn't have survived had we done it any other way.”

— Sander Daniels

Once you’ve decided how to constrain your marketplace, you then need to pick which side of the marketplace to put most of your resources behind (supply or demand). In our next post, learn how today’s biggest marketplace companies decided whether to concentrate on supply vs. demand early-on, plus how one “marketplace” realized they weren’t a marketplace after all.

Next post (coming later this week):

Part 1: Constrain the marketplace 🔬 (this post)

Part 2: Decide which side of the marketplace to concentrate on 🧐

Part 3: Drive initial supply 🐥

Part 4: Drive initial demand 👋

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2qnzckI