Monzo: We built network isolation for 1500 services

In the Security team at Monzo, one of our goals is to move towards a completely zero trust platform. This means that in theory, we'd be able to run malicious code inside our platform with no risk – the code wouldn't be able to interact with anything dangerous without the security team granting special access.

The idea is that we don't want to trust just anything simply because it's inside our platform. Instead, we want individual services to be trusted based on a short and deliberate list of which other services they're allowed to interact with. This makes an attack substantially more difficult.

We've been investigating network isolation

As we work towards a zero trust platform, we've spent part of the last year investigating network isolation. In practice, this means we don't want the service that controls the images on Pots to be able to talk to a service that moves money. Services should have specifically defined and manually approved lists of what they can communicate with, and anything else should be blocked.

With a handful of services, we could probably maintain these lists manually. But we already have over 1,500 services, and so the list of allowed paths is huge and constantly changing. In fact, there are over 9,300 unique connections (for example, from service.emoji to service.ledger).

But the number of services and connections in our platform makes this difficult

The sheer number of services and connections made this project really challenging. We had to figure out a way to generate allowed paths from our code, store the rules in a way that was easy for engineers to manage and for machines to interpret, and then enforce them without breaking anything.

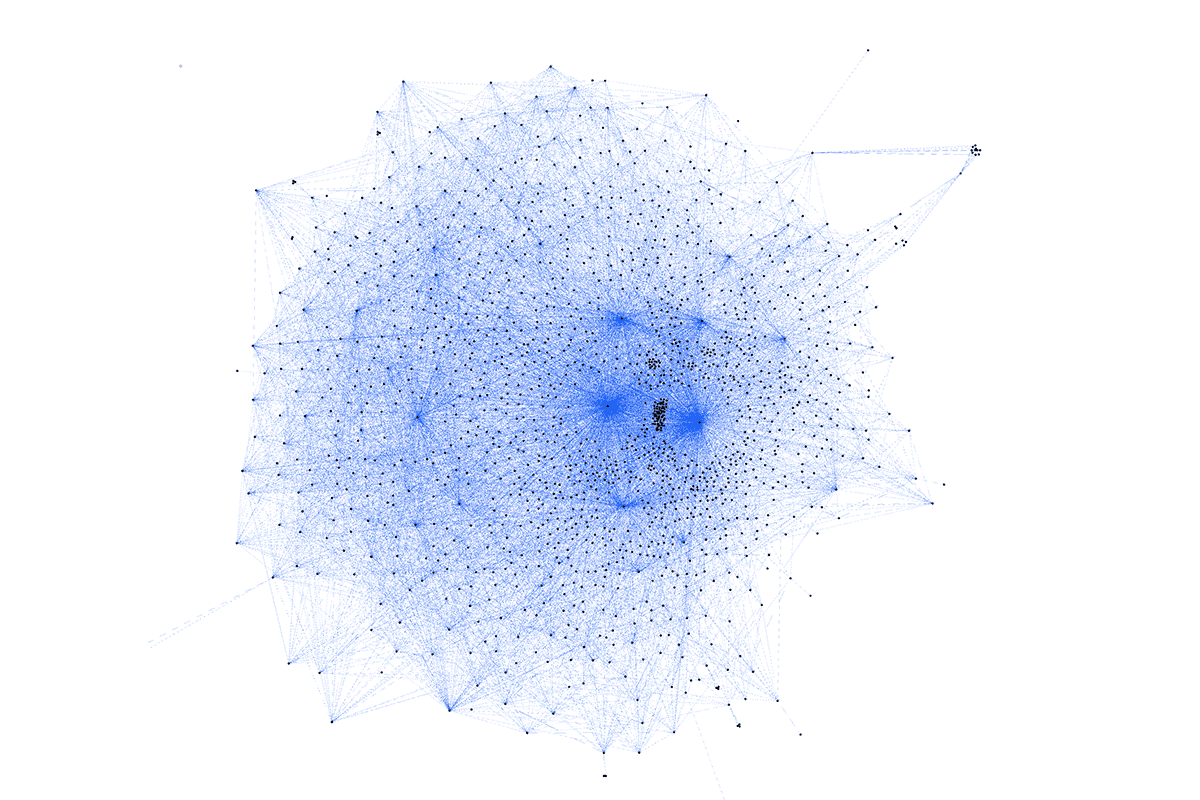

Here's the network we specified as part of this project. Each services is represented by a dot. And every line is an enforced network rule that allows communication between two services.

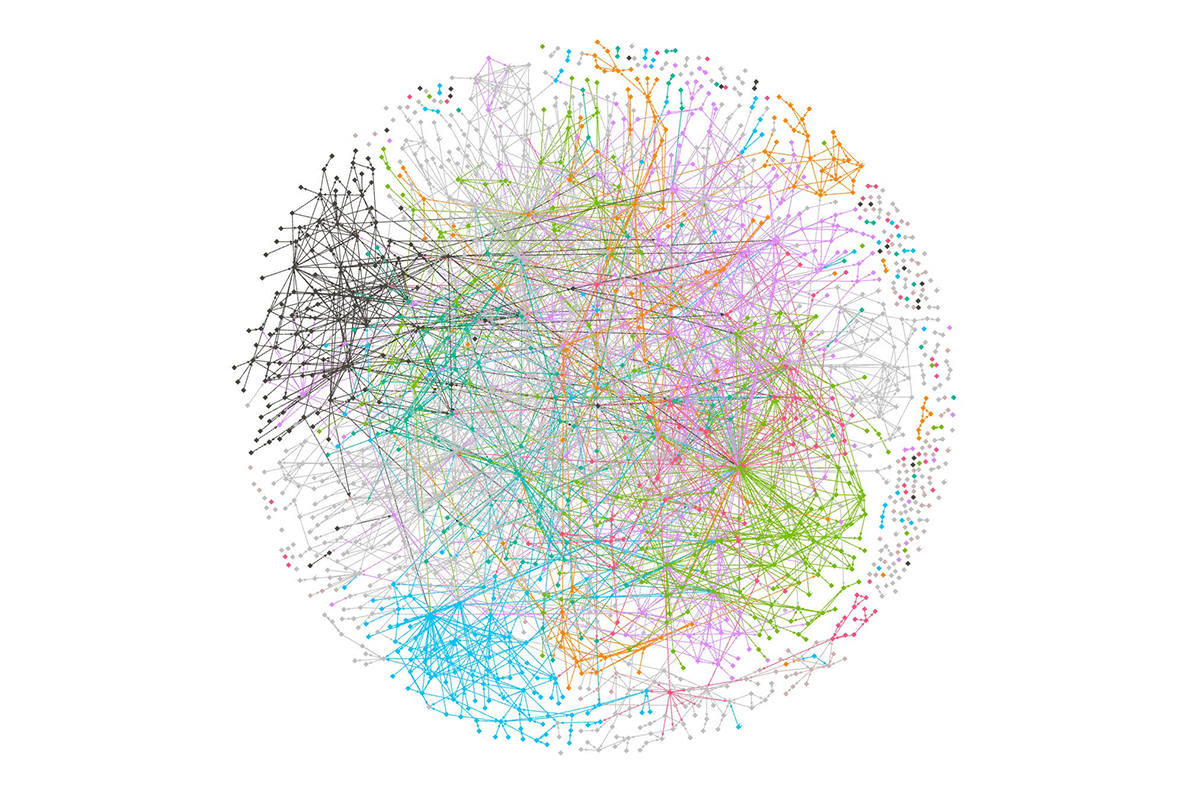

Here's the same graph with a few popular nodes removed, and coloured by team:

If you're interested in why we decided to build this kind of system, check out this blog post we wrote back in 2016 about building a modern backend, or this talk by one of our engineers about how we use microservices.

First, we isolated one service as a trial

Before we ever decided to apply isolation to all services, we decided to apply it to one of our most high-security services, service.ledger. This is the source of truth for our customers' balances, and all money movements. One of our engineering principles is to ship projects and then iterate, so it's best to start small especially with such a complex system. The reason we picked such an important service first is that the finance team really wanted to lock down this service in particular and were keen to help us in our trial.

We came up with a tool to analyse our code

To start we wrote a tool called rpcmap. This would read all the Go code in our platform, and attempt to find code that looked like it was making a request to another service. In doing so, the tool maps out the connections between our services and the services they call. This wasn't perfect, but it was good enough to build a list of services that need to call the ledger. We then manually checked this list to make sure it was accurate.

We ended up with a simple list of services. Next, we wanted to enforce that only services in this list could make requests to the ledger. And we knew we could use a very straightforward feature of Kubernetes (the software that orchestrates our services) called the NetworkPolicy resource to do that. The policy was part of the ledger configuration and simply listed a set of allowed calling services. Only traffic from sources with the right labels is allowed: for example we allow services that are labelled as service.pot.

When an engineer needs to add a new caller to the ledger, they add it to this list and redeploy the ledger. We store the above file in the same place as the ledger's code, so that when you change it, the finance team have to review it. This lets them keep track of who's calling such a critical service, which is important to make sure that we're in control. We have an automated check running on new code that reminds engineers to whitelist their calling service if they call the ledger.

But our trial highlighted issues with this approach

This approach worked well for the ledger, but we knew it wouldn't be possible to scale it to all our services for a few reasons:

We didn't have a safe way to test these policies before rolling them out, and it was too manual to check policies we'd generated. We need to be able to roll out a policy and know definitively if it would drop traffic, without actually dropping the traffic. This would let us generate policies automatically instead of checking them manually, then simply wait a few days to see if they're correct.

While it worked well for the ledger, teams don't always want to review every new caller of their service. So it's not ideal that the list of allowed services was a property of the receiving service.

Engineers would have to edit Kubernetes configuration files to do this whitelisting. This isn't something they're generally used to doing, and so is prone to errors.

Rolling back a service becomes really risky. If you go back to an earlier version of a service to correct a code change, you might also roll back to before a calling service was whitelisted, blocking its traffic suddenly. This highlights a fundamental problem with this approach.

service.emojicallsservice.ledgeris a property ofemojiand should be deployed as such. But above we make it a property ofledger. The whitelist of services becomes shared state, which can get out of sync and is hard to maintain. We wanted to follow the single responsibility principle.

So we decided to look for ways of testing policies, and rethink where we defined the rules.

We investigated ways to test policies safely

We actually implement our Kubernetes network policies using Calico, which is networking software that lets our services talk to each other. We spoke to the Calico community about testing network policies, and found that we could use some features of Calico that aren't accessible through Kubernetes to make our policies testable.

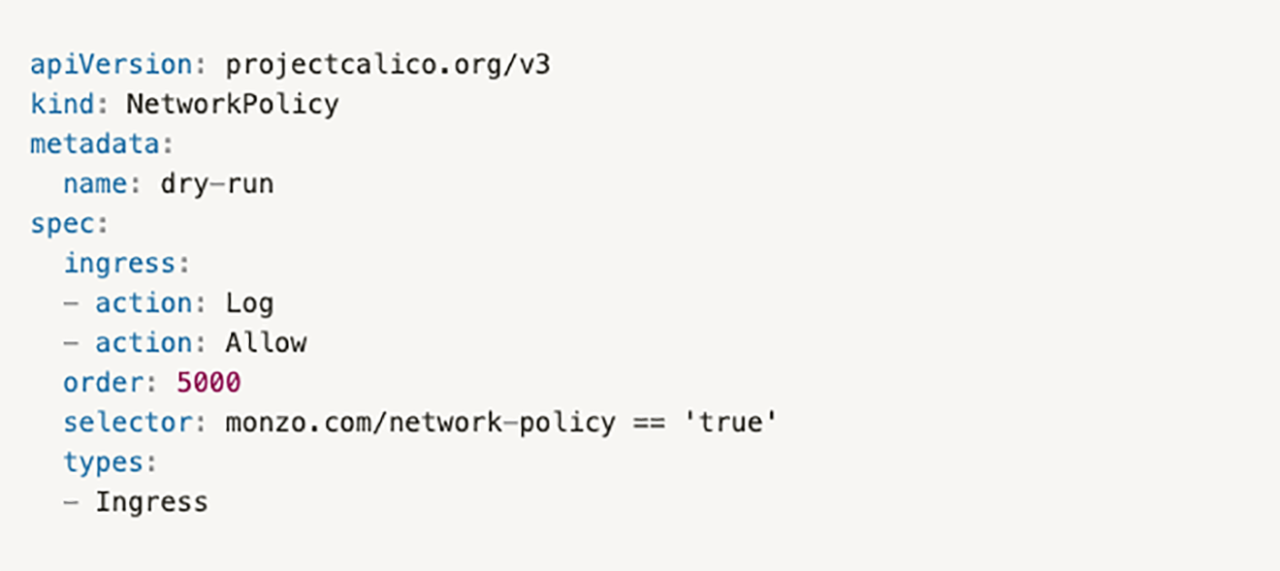

Whenever we'd applied a network policy to a service, we decided to label it. We then used a Calico network policy, which has some extra features beyond what Kubernetes gives us, to make the following statement:

If traffic comes into a service that has a network policy on it

And the traffic would not be allowed by its policy

Then log the traffic, and allow it

Here's what that policy looks like:

Essentially, this policy runs after any Kubernetes network policies because of its high order field. So if traffic reaches this policy, it mustn't have been allowed by the Kubernetes policies.

The ability to only select on services that already have policies was crucial. Otherwise, a dry run policy like the one above would capture all traffic for services without a policy of their own, and we wouldn't know how much traffic would have been dropped if the dry run policy didn't exist.

We used some tools to get visibility into our network

With this dry run policy, no traffic would ever be dropped by our policies. And we'd also get a log entry whenever it would have been dropped. We watched these logs with a handy tool called kube-iptables-tailer, so that we could create graphs showing which services are dropping traffic and from where.

We were a little concerned that too much logging (from an incorrect policy that would drop a load of traffic) would create problems in our platform. So we decided to only turn on logging after we'd proven the rate would be low. To do that, we wrote a new tool, calico-accountant, which was able to count how many packets would be dropped for a given service, without actually logging them. This count was useful to see which services had bad policies. But we still needed logs in some cases, because the logs also show the source service for the 'dropped' traffic.

Even once we started enforcing network policies so that they'd drop disallowed traffic, we kept the logging enabled so we could quickly alert engineers to dropped traffic, from a bug or an attacker.

We redesigned how to represent connected services

We thought a lot about our hypothesis that traffic from service.emoji to service.ledger should be represented as a property of emoji, and came up with quite a few ideas. We essentially wanted each service to somehow specify what other services it needed to talk to, then sum these up to figure out the inbound services for ledger.

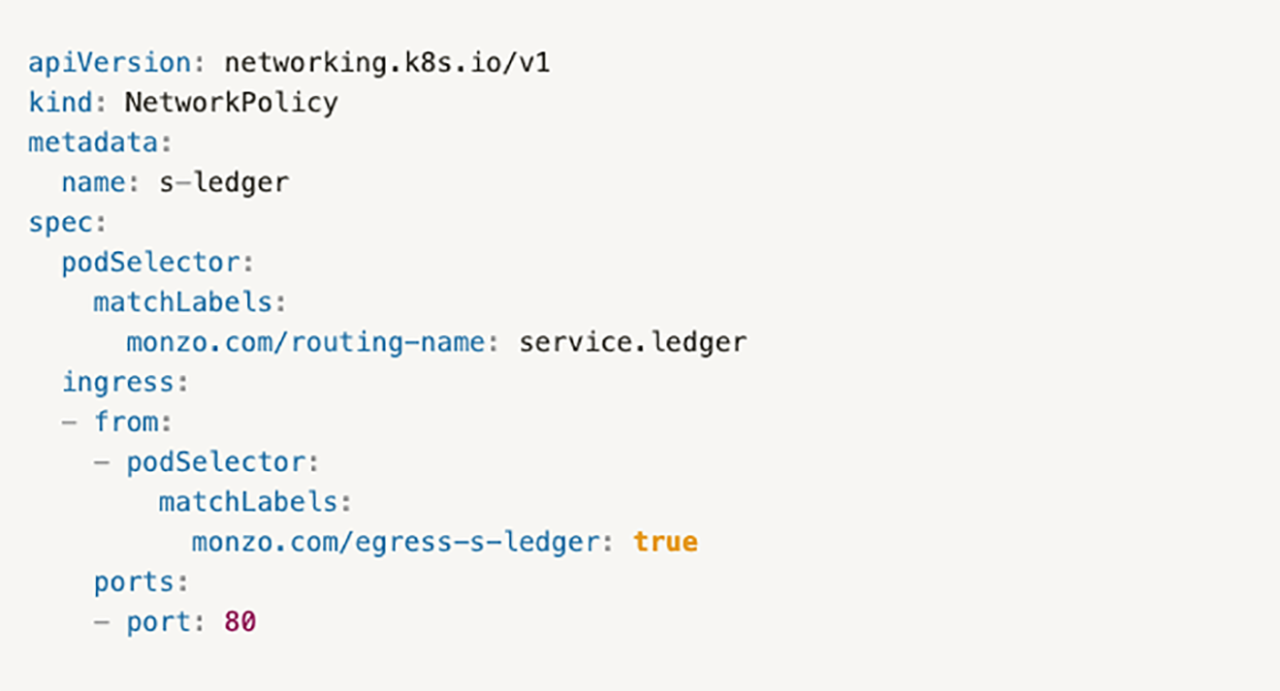

At first, we thought of writing one network policy per link (emoji → ledger). But the number of policies would've led to big performance issues. We then realised that we could simply label services with what they need. If you needed to talk to service.ledger, you could have a label like monzo.com/egress-s-ledger. Then the ledger network policy could look like this:

This was a key breakthrough! We now had a straightforward, identical policy to write for all services, and a very simple way to denote what destination services a calling service has.

We wrote some policies that applied to many services

We knew we'd also have to cover services that need to talk to large groups of services. For example, our monitoring services talk to pretty much everything. We don't want to have to label the monitoring service with every single service in the platform, as it's a huge and constantly changing list.

We could have added something to every service's policy to allow monitoring. But then to add a new service which calls everything, we'd have to deploy all services with a new policy. We decided instead to add another label, service-type, which loosely groups services by what needs to call them.

For example, if you have the backend service type label, you can be called by one group of services. If you have the api label, you have a slightly different group. We enforce this with some 'catch-all' policies like this:

These policies only select on things that already have network policies, which mean they can only allow new traffic, and have no risk of blocking any traffic.

We came up with a way for engineers to manage these rules

The above is a really nice way to instruct computers what paths are allowed. But it would be a nightmare if we expected our engineers to keep these labels updated themselves. We can't ask people to think about whether they need to whitelist a service, then convert the service name into the label, and then find the right configuration file to add that label into. Instead, we wanted to completely automate this process.

First, we updated

rpcmapso that if we ran it on a service, it would scan it for whatever it calls, and generate 'rule files'. This is simply a file per called service that represents the fact that A calls B. So,service.emojiwould have a fileservice.emoji/egress/service.ledger.rule.We set up

rpcmapto run on everyone's code whenever they push their code to GitHub. This reminds engineers to keep the rules updated. It also checks the rule files before it accepts code. And of course the rule files also need to be reviewed by a human.If a team wants to keep track of callers to their critical services, they can instruct GitHub to ask for their review on

*/service.ledger.rule. So they'll be asked to review the rule file even though it resides inside another team's service.Next, we updated our deployment pipeline to convert the above rule files into labels for the services. We were able to maintain the ability to make calls to a service reviewable by the owner of the destination service, and make the links between services really easy to understand. This also makes it really easy to figure out what services call the ledger – you simply look for files named

service.ledger.rule. The nice thing about enforcing rules on our platform is that it gives us provable information – we know that the list of callers of the ledger is exhaustive.

We rolled out to 1,500 services

With all these controls in place, we were able to roll out fairly rapidly despite the huge number of services. First, we generated rule files for all services, and started enforcing that they're maintained for code to be accepted. From this moment on, we had a reasonably accurate network of connected services.

Next, we rolled out all the network policies into our test environment, which is identical to the platform that actually runs Monzo. In doing so, we discovered and fixed a bunch of cases where rpcmap wasn't able to infer that a service called another service, as these showed up as dropped traffic. We generally fixed those cases by adding a special comment in the code that told rpcmap about the link:

We also had to manually cover non-Go services (we don't have very many). Within a couple of days we'd fixed all the drops in our test environment, so we changed the dry run policy so we'd now drop disallowed traffic.

Now, we could be more confident that engineers wouldn't accidentally ship code that didn't have appropriate rule files, because the code would fail in the test environment.

Next, we rolled out the network policies to our production platform, with packet dropping and logging disabled, but with alerts that would fire if anything violates the rules (already a big win for security). We also kept logging disabled because of the potential for huge log volumes, until we'd rolled out all the labels which allow traffic. Once we'd proven that log volume would be small using calico-accountant, we enabled logging of dropped traffic to find remaining missed cases where rpcmap wasn't clever enough. This let us get the dropped count down to zero.

We've decided to leave packet dropping turned off for a month, to be sure that there aren't any paths that are very rarely used that might no longer be allowed. We still get a lot of security value from alerting on violations, but we'll also be turning on packet dropping when we're completely sure that nothing will ever be dropped as part of normal business processes.

Now, a service can only call six others on average

We've moved from every service being able to call 1,500 others, to every service being only able to call six others on average, with review of every new pairing. Solving the human issues around managing these rules was a particularly interesting challenge. And it's been an incredible win for security and a huge step towards a zero trust platform.

If you find this project interesting, we're hiring! Head to monzo.com/careers to see all our open roles in defensive and offensive security 🚀

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2PPzxXG