New research: Dark Energy might not exist after all

The observed acceleration of the Hubble expansion rate has been attributed to a mysterious "dark energy" which supposedly makes up about 70% of the universe. Professor Subir Sarkar from the Rudolf Peierls Centre for Theoretical Physics, Oxford along with collaborators at the Institut d'Astrophysique, Paris and the Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen have used observations of 740 Type Ia supernovae to show that this acceleration is a relatively local effect—it is directed along the direction we seem to be moving with respect to the cosmic microwave background (which exhibits a similar dipole anisotropy). While the physical reason for this acceleration is unknown, it cannot be ascribed to dark energy which would have caused equal acceleration in all directions.

Professor Sarkar explains: "The cosmological standard model rests on the assumption that the Universe is isotropic around all observers. This cosmological principle is an extension of the Copernican principle—namely that we are not privileged observers. It affords a vast simplification in the mathematical construction of the cosmological model using Einstein's theory of general relativity. However when observational data are interpreted within this framework we are led to the astonishing conclusion that about 70% of the universe is constituted of Einstein's Cosmological Constant or more generally "dark energy." This has been interpreted as due to quantum zero-point fluctuations of the vacuum but the associated energy scale is set by H0, the present rate of expansion of the universe. This is however a factor of 1044 below the energy scale of the standard model of particle physics—the well-established quantum field theory that precisely describes all subatomic phenomena. Its zero-point fluctuations have therefore a huge energy density which would have prevented the universe from reaching its present age and size if they indeed influence the expansion rate via gravity. To this cosmological constant problem must be added the "why now?" problem, namely why has dark energy come to dominate the universe only recently? It was negligible at earlier times, in particular at an age of ~400,000 years when the primordial plasma cooled sufficiently to form atoms and the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation was released (hence the CMB is not directly sensitive to dark energy)."

It is against this background that he, along with Jacques Colin and Roya Mohayaee (Institut d'Astrophysique, Paris) and Mohamed Rameez (Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen), set out to examine whether dark energy really exists. The primary evidence—rewarded with the 2011 Nobel prize in physics—concerns the "discovery of the accelerated expansion of the universe through observations of distant supernovae" in 1998 by two teams of astronomers. This was based on observations of about 60 Type Ia supernovae, but meanwhile, the sample had grown, and in 2014, the data was made available for 740 objects scattered over the sky (Joint Lightcurve Analysis catalog).

The researchers looked to see if the inferred acceleration of the Hubble expansion rate was uniform over the sky.

"First, we worked out the supernova redshifts and apparent magnitudes as measured (in the heliocentric system), undoing the corrections that had been made in the JLA catalog for local 'peculiar' (non-Hubble) velocities. This had been done to determine their values in the CMB frame in which the universe should look isotropic—however, previous work by our team had shown that such corrections are suspect because peculiar velocities do not fall off with increasing distance, hence there is no convergence to the CMB frame even as far out as a billion light years," says Professor Sarkar.

Dark energy

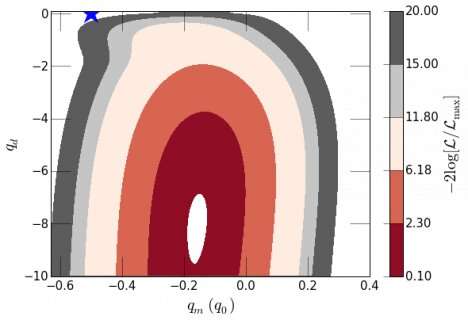

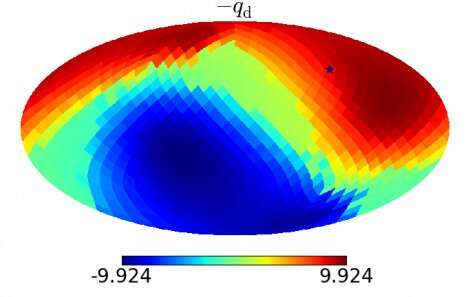

"When we then employed the standard maximum likelihood estimator statistic to extract parameter values, we made an astonishing finding. The supernova data indicate, with a statistical significance of 3.9σ, a dipole anisotropy in the inferred acceleration (see figure) in the same direction as we are moving locally, which is indicated by a similar, well-known, dipole in the CMB. By contrast, any isotropic (monopole) acceleration that can be ascribed to dark energy is 50 times smaller and consistent with being zero at 1.4σ. By the Bayesian information criterion, the best fit to the data has, in fact, no isotropic component. We showed that allowing for evolution with redshift of the parameters used to fit the supernova light curves does not change the conclusion—thus refuting previous criticism of our method.

"Our analysis is data-driven but supports the theoretical proposal due to Christos Tsagas (University of Thessaloniki) that acceleration may be inferred when we are not Copernican observers, as is usually assumed, but are embedded in a local bulk flow shared by nearby galaxies, as is, indeed, observed. This is unexpected in the standard cosmological model, and the reason for such a flow remains unexplained. But independently of that, it appears that the acceleration is an artifact of our local flow, so dark energy cannot be invoked as its cause.

"There are, indeed, other probes of our expansion history, e.g. the imprint of baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) in the distribution of galaxies, the ages of the oldest stars, the rate of growth of structure, etc., but such data is still too sparse, and presently equally well consistent with a non-accelerating universe. The precisely measured temperature fluctuations in the CMB are not directly sensitive to dark energy, although its presence is usually inferred from the sum rule that while the CMB measures the spatial curvature of the universe to be close to zero, its matter content does not add up to the critical density to make it so. This is, however, true only under the assumptions of exact homogeneity and isotropy—which are now in question."

Professor Sarkar concludes: "But progress will soon be made. The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope will measure many more supernovae and confirm or rule out a dipole in the deceleration parameter. The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument and Euclid satellite will measure BAO and lensing precisely. The European Extremely Large Telescope will measure the 'redshift drift' of distant sources over a period of time, and thus make a direct measurement of the expansion history of the universe."

Jacques Colin et al. Evidence for anisotropy of cosmic acceleration,

Astronomy & Astrophysics(2019).

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201936373Citation: Evidence for anisotropy of cosmic acceleration (2019, November 27) retrieved 28 November 2019 from https://ift.tt/2QZ36GD

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2QZ36GD