Things That Go Bump in the Stacks (2014)

In honor of Halloween, this week's blog post focuses on several of Special Collections' 17th century publications about witchcraft, demonology, and exorcism. Works on these subjects were produced during the Renaissance in both Protestant and Catholic nations as the Catholic Church, which had been the supreme religious authority in Europe during the Middle Ages, came under heavy attack from Protestant reformers, monarchs, and others. In response to these challenges, the Catholic Church expanded the scope and reach of the Inquisition, a branch within the Church's judicial system dedicated to maintaining Catholic orthodoxy and combatting heresy.

In honor of Halloween, this week's blog post focuses on several of Special Collections' 17th century publications about witchcraft, demonology, and exorcism. Works on these subjects were produced during the Renaissance in both Protestant and Catholic nations as the Catholic Church, which had been the supreme religious authority in Europe during the Middle Ages, came under heavy attack from Protestant reformers, monarchs, and others. In response to these challenges, the Catholic Church expanded the scope and reach of the Inquisition, a branch within the Church's judicial system dedicated to maintaining Catholic orthodoxy and combatting heresy.

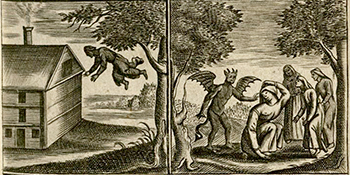

Prosecution of witches in particular was more common during the Renaissance than it had been previously. Published in London, Joseph Glanvil's Saducismus Triumphatus: Or, Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions, describes a witch as a person "who can do or seems to do strange things, beyond the known Power of Art and ordinary Nature, by v[i]rtue of a Confederacy with Evil Spirits." He goes on to stipulate that the "strange things" must be real, not illusions, and that the witch must have made a covenant or compact with an "Intelligent Creature of the Invisible World, whether one of the Evil Angels called Devils, or an Inferiour Dæmon or Spirit … one that is able and ready for mischief." (Part II, p. 4)

Though either men or women could be accused of witchcraft, women were accused of the crime most frequently. In many texts, including Glanvil's and Francis Hutchinson's An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft, also published in London, feminine pronouns are used almost exclusively in discussions of witches and witchcraft. Hutchinson's book includes an entire chapter on the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts, and another devoted to identifying witches via their teats, marks, charms, inability to cry, and ability to float or swim in water, the last two characteristics considered particularly unnatural for a woman.

Though either men or women could be accused of witchcraft, women were accused of the crime most frequently. In many texts, including Glanvil's and Francis Hutchinson's An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft, also published in London, feminine pronouns are used almost exclusively in discussions of witches and witchcraft. Hutchinson's book includes an entire chapter on the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts, and another devoted to identifying witches via their teats, marks, charms, inability to cry, and ability to float or swim in water, the last two characteristics considered particularly unnatural for a woman.

Alleged incidents of demonic possession were often investigated by the Inquisition. Those found guilty were usually tortured, then burned alive at the stake. Numerous volumes on demonic possession and exorcism were written at the time, often in vernacular languages rather than Latin, in an effort to educate clergy and others about demonic possession and how to combat it. Published in Rouen, France, Brother Sanson Birette's Refutation de l'Erreur du Vulgaire, Touchant les Responses des Diables Exorcizes (Refutation of the Error of the Vulgar, Regarding the Responses of Exorcised Devils), includes a lengthy section explaining how to best use God's power to harm or injure devils.

Two additional works published in Venice focused on the exorcist's methodology, including Flagellum Dæmonum, Exorcismos Terribiles, Potentissimos, et Efficaces (Demons' Scourge: Terrible Exorcisms, Powerful and Effective). This work includes sections on detecting demons that besieged human bodies, and the most effective ways to drive demons out of the possessed. The Compendio dell'Arte Essorcistica (Compendium of the Exorcism Arts) includes a lengthy explanation that purports to prove demons are real in response to contemporary challenges to their existence, followed by detailed descriptions of techniques that had been successfully used to combat them.

Two additional works published in Venice focused on the exorcist's methodology, including Flagellum Dæmonum, Exorcismos Terribiles, Potentissimos, et Efficaces (Demons' Scourge: Terrible Exorcisms, Powerful and Effective). This work includes sections on detecting demons that besieged human bodies, and the most effective ways to drive demons out of the possessed. The Compendio dell'Arte Essorcistica (Compendium of the Exorcism Arts) includes a lengthy explanation that purports to prove demons are real in response to contemporary challenges to their existence, followed by detailed descriptions of techniques that had been successfully used to combat them.

Still others addressed the general "magical arts," including demonic possession and witchcraft. One work, titled Disquisitionum Magicarum Libri Sex (Magical Inquiries in Six Parts) discusses myriad topics including the possibility of mortals conceiving children with demonic beings, especially incubi and succubi. It concludes with a section devoted to confession, penance, and forgiveness for the formerly possessed, making it clear that the burden for requesting forgiveness rests with the person who interacted with demonic spirits. The Church expected such individuals to confess the events of their transgressions to a priest to avoid eternal damnation.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2Cfj4UJ