A Stanford Professor Says Juul Stole Her Anti-Vaping PowerPoint Slides

SAN FRANCISCO — When vape pens began flooding classrooms, bewildered teachers didn’t know what to do about it. Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, a Stanford University pediatrics professor who had spent years researching how to get kids to stop smoking, did what came instinctively to her: She educated them.

By 2018, she’d created a free online class for middle and high schoolers about the dangers of e-cigarettes. That year, she updated her course to explicitly call out one up-and-coming brand in particular: Juul. The biggest e-cigarette manufacturer in the country, Juul has been accused by public health advocates and regulators of creating a new generation addicted to nicotine at a time when youth smoking rates have been dropping to historic lows.

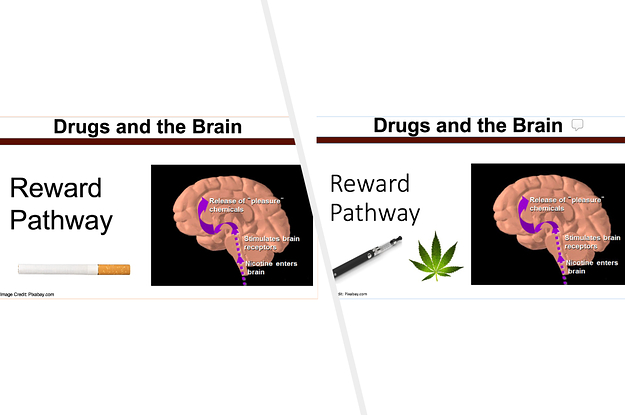

So she was surprised to learn around that time that Juul, too, had an anti-vaping curriculum — and was offering thousands of dollars to schools to implement it. When she got ahold of what Juul wanted to teach, she was even more surprised: Many of its slides were copies of hers, down to the exact words and cartoon images of the brain.

But Juul hadn’t asked to use them. And the rest of its slides, in her view, dangerously downplayed the addictive aspects of Juuling. The company’s presentation didn’t discuss how flavors attract children, for instance, or how the chemicals in flavors can be harmful, or that a Juul pod contains as much nicotine as a pack of cigarettes. Her slides without this context presented what the Stanford professor felt was a deliberately rosy picture of Juul’s health effects.

Do you work, or have you worked, at Juul? Contact this reporter at stephanie.lee@buzzfeed.com or stephaniemlee@protonmail.com. Visit tips.buzzfeed.com for other secure ways to get in touch.

In another misleading move, the materials Juul circulated said that the class was based on Stanford’s, giving some educators the false impression that the professor worked alongside the company to develop its anti-vaping curriculum. “That’s when I said, ‘This is not OK,’” Halpern-Felsher recalled.

Juul, whose stated mission is to help adult smokers quit, has denied that it ever marketed to teens. But studies have reached the opposite conclusion, finding that, particularly in the company’s early days in 2015 and 2016, it hired influencers to make #juul go viral, handed out free devices at concerts and movies, and ran colorful “Vaporized” ads that featured twentysomethings and mimicked cigarette ads.

Today, 28% of high school students use e-cigarettes, and more schools by the day are suing Juul on the basis that their students’ habits are a financial burden. Parents are suing, too, saying that their kids are addicted to Juuling. Lawmakers, struggling to find a policy approach that would actually work, just succeeded in changing the federal age for smoking and vaping from 18 to 21.

And Juul is responding to the scrutiny, too. This fall, the company suspended all its advertising in the US and stopped US sales of all its flavors, long a big draw for young users, except for tobacco and menthol. Although the $24 billion San Francisco startup laid off some 600 employees last month, it is still staffing up its youth-prevention team and hired a prominent teen nicotine addiction researcher to help lead those efforts.

But Halpern-Felsher is unconvinced that Juul — which is partially owned by tobacco giant Altria and run by a former Altria executive — has proven it can be trusted to police itself.

“How do we know they’re not going to repeat what they’ve already been doing, when they clearly have a history over the last three years of attracting youth?” she told BuzzFeed News.

Stanford's Tobacco Prevention Toolkit, Juul's curriculum obtained in May 2018, Juul's curriculum obtained in June 2018

Even after receiving a cease-and-desist letter from Stanford’s lawyers in April 2018, Juul kept circulating versions of Halpern-Felsher’s materials with tweaks, according to PowerPoint slides seen by BuzzFeed News. And although Juul publicly said it abandoned the curriculum a month later, shortly after introducing it, the startup’s employees continued to pitch educators on using it into that summer, new emails show.

A Juul representative declined to comment on these allegations. In a statement, spokesperson Ted Kwong acknowledged that the company “discontinued the initiative in 2018 in response to feedback from those who thought our efforts to dissuade youth from using nicotine were being misunderstood.”

He added, “We fully understand the need to earn back the trust of regulators, policymakers, key stakeholders and society at large and reset our company and the vapor category.”

Halpern-Felsher, who was the first to sound the alarm about Juul’s curriculum in an October 2018 journal article, has spoken before about the unsanctioned use of her materials, most recently during a July Congressional hearing. Emails from Juul representatives and slide-by-slide comparisons of the courses are printed here for the first time.

In under two years, the Stanford class — which is meant to be an alternative to suspension — has become a key tool in the fight against the teen e-cigarette craze. More than 1.1 million students have sat through it and more than 2,000 teachers have been trained to teach it. And it seems to be working: In a survey of 325 students, the percentage who said they were “very unlikely” to try Juuling jumped from 74% to 89% after they took the class, according to preliminary data from Halpern-Felsher’s team. Students were also more likely to come away thinking of Juuling as “highly addictive” (38% before the class compared to nearly 50% afterward).

In contrast, there is no evidence that tobacco industry–sponsored youth-prevention programs decrease use. Instead, they are viewed by many as a more sinister form of marketing.

If Juul’s stated purpose is to help adults quit smoking, “then why are you going into schools and talking about your product, period?” Halpern-Felsher said. “We see it as a ploy, in my opinion, to be able to get into these schools to have a dialogue about their product and not be fully honest.”

The first time that California educators got wind of Juul’s curriculum was in December 2017.

A company memo, sent to the then head of California’s Department of Education a few weeks before Christmas, said that as part of a broader youth-prevention strategy, Juul was designing an educational program that would be an alternative “to traditional prevention programs and discipline.” The curriculum was “drawing on best practice resources, such as Stanford Medicine,” the memo said, as well as from a nonprofit and two public health programs.

A colleague forwarded the memo to Halpern-Felsher, who found the reference confusing but didn’t think to dive deeper. A developmental psychologist at Stanford since 2014, Halpern-Felsher studies what drives adolescents to make risky health decisions, from drinking alcohol and having sex to drunk driving and, especially recently, smoking. In the fall of 2016, she and her team created the Tobacco Prevention Toolkit, an online class that covered nicotine addiction to both cigarettes and e-cigarettes.

Not long after, she kept hearing about one particular e-cigarette brand: Juul. With their sleek, USB drive-like design, high doses of nicotine, and sweet, fruity flavors, Juulswere popping up in cafeterias and teenage bedrooms everywhere.

As the company rose to become the market leader, Halpern-Felsher heard that it was developing a youth-prevention curriculum. Urged by educators to come up with one of her own, she added a section specifically about Juul to the e-cigarette portion of her Toolkit. It went online on Feb. 1, 2018.

Five days later, in Sacramento, a Juul representative pitched the company’s class at a meeting of California’s statewide tobacco-prevention education committee. Bruce Harter, a Bay Area superintendent turned Juul consultant who’d been reaching out to school districts on the company’s behalf, insisted that Juul was “appalled and distressed” by underage use and reassured attendees that it was “interested in promoting health,” according to meeting minutes.

Halpern-Felsher wasn’t there. But she was alarmed to hear about it — and to learn that academics were getting the impression that her curriculum was affiliated with Juul’s.

Over the following weeks, Halpern-Felsher sought to get her hands on Juul’s curriculum. It wasn’t available online, so she relied on people sending her bits and pieces of it. Her fear was confirmed when she was sent the company’s syllabus: It described the science portion as “drawn largely from the work of Stanford Medicine,” and linked to Halpern-Felsher’s Tobacco Prevention Toolkit.

That spring, school districts were being offered as much as $10,000 to $20,000 to implement Juul’s curriculum. In a February email, a California state education official told schools that the curriculum was considered an attempt to “coerce” schools “to support the addiction of youth to nicotine.”

Scott Gerbert, who works in tobacco-prevention education for Alameda County schools in the Bay Area, remembers getting a call from a health educator and anti-smoking advocate he used to work with, Deborah Messina-Kleinman. She was about to accept a job at Juul, she told him, and wanted to provide his district with educational materials. Gerbert quickly hung up.

“I certainly would not invite Juul in to be a partner in education,” Gerbert said, “the same way we would not invite Anheuser-Busch in or Altria or any of the other Big Tobacco companies.” (Messina-Kleinman did not return a request for comment.)

And one day in New York, Meredith Berkman’s ninth-grade son came home to tell her that he and his classmates had just listened to a Juul representative — with no teachers present — reassure them that Juuling was “totally safe,” Berkman said. (Berkman did not know whether this was an official presentation of the Juul curriculum.) Horrified, she and two other mothers went on to found the national advocacy group Parents Against Vaping E-cigarettes, which Halpern-Felsher advises.

"You don’t typically expect companies to be trusted to educate the public about themselves."

Not even everyone inside Juul thought the program was a smart move.

When then-CEO Kevin Burns announced the new initiative at an all-hands meeting in the early spring of 2018, no one openly questioned him, according to a Juul employee present for the meeting who spoke to BuzzFeed News on the condition of anonymity. But in private discussions afterward, several employees agreed that the move was “misguided.”

“You don’t typically expect companies to be trusted to educate the public about themselves,” the individual said. “Juul is obviously not an impartial purveyor of information.”

And in internal emails unearthed by a congressional investigation, Juul employees spearheading the effort acknowledged the youth-prevention programs were “eerily similar” to those used by Big Tobacco.

In early April 2018, based on what Halpern-Felsher had heard about and seen so far of the Juul curriculum, Stanford lawyers sent a cease-and-desist letter to the company. In response, Juul attorneys said that the company had never linked to Stanford — despite evidence to the contrary — and wouldn’t link to any materials in the future, and claimed that it wasn’t using the Toolkit, according to Halpern-Felsher.

In May, Juul sent a letter asking her to meet; she declined. It also asked her to change what it perceived as unfounded opinions and statements about Juul in the Toolkit. Halpern-Felsher said that the curriculum wasn’t inaccurate, but she made some minor changes, including changing her course’s title from exclusively calling out Juul to “Juul and Other Pod-Based Systems.”

She also added a disclaimer stating that the Toolkit was not affiliated with any e-cigarette companies, and any implication otherwise was “simply not true.”

From left: Stanford's Tobacco Prevention Toolkit, Juul's curriculum obtained in May 2018, and Juul's curriculum obtained in June 2018.

Around the same time, a colleague finally sent Halpern-Felsher a complete copy of Juul’s class. A lot of it looked awfully familiar.

Most of the two dozen or so slides in its “science of e-cigarettes” PowerPoint were nearly or fully identical to the nicotine-addiction slides that she’d first put up back in 2016, according to screenshots she captured. Echoing the layout, colors, language, and images, the slides showed graphics of brain synapses and discussed the “work in progress” that is the adolescent brain. Even the accompanying teacher talking points and PowerPoint comments from Halpern-Felsher’s lab members, visible only in editing mode, appeared to be copied over. “Would love for this to be animated,” a research assistant noted on one slide.

Halpern-Felsher said there’s nothing inherently wrong with teaching teens about nicotine addiction, “aside from the fact you can’t steal someone else’s curriculum and pretend it’s yours and push back when we tell you not to.”

The real problem, in her view, was this: Even though the class acknowledged that nicotine is highly addictive, it failed to connect the dots to Juuling. It didn’t mention, for instance, that a single 5% Juul pod contains as much nicotine as a pack of cigarettes — more than many other e-cigarettes on the market, and almost triple the legal maximum for pods in Europe.

“If you’re really trying to prevent people from using your product, then your curriculum would be about the harms of your product,” Halpern-Felsher said. “We know they do not make any of those connections.”

In addition, Juul’s curriculum taught mindfulness meditation practices as a technique to avoid vaping, even though there isn’t evidence that they are an effective tobacco-prevention strategy in schools.

And there was an evaluation worksheet, ostensibly to test students’ knowledge of the lesson, that asked: “What’s appealing about using e-cigarette or JUULs? Why do students use them?” To Halpern-Felsher, this question belonged in a marketing survey, not an educational program.

“If I know the kids are using it because of flavors, or it’s cool, that’s fantastic — I can use that information to turn it around and market it back to kids again,” she said.

In the end, Juul distanced itself from the curriculum. The company has said it stopped distributing its curriculum in May 2018, not long after the whole idea was hatched, after blistering criticism from anti-tobacco advocates and government regulators.

But for at least another month, Juul kept promoting the curriculum to educators, emails show.

From left: Stanford's Tobacco Prevention Toolkit, Juul's curriculum obtained in May 2018, and Juul's curriculum obtained in June 2018.

On June 7 of that year, Julie Henderson, Juul’s director of education and youth prevention, emailed the slides to a health educator in Connecticut and offered to collaborate on outreach. “Our efforts are not limited to adolescents, but include young adults as well so we welcome the opportunity to work with colleges and universities in promoting non-nicotine use among non-smokers,” Henderson wrote.

And on June 22, Samanta Beltran, a youth prevention and communications analyst at Juul, similarly responded to an inquiring educator in Orange County, California. “If you’re interested in developing a partnership with us, whether through use of curricula or a co-convened community conversation, please let us know,” she wrote, attaching the slides.

Henderson and Beltran did not return requests for comment.

This version of the curriculum, which was sent to Halpern-Felsher, did differ from the earlier version she had seen. The white background was now blue. “The Adolescent Brain: A Work In Progress” became “Your Brain: Still Developing.” A photo of overlapping freeways, meant to illustrate the complexity of a young adult’s brain, was swapped for one of tangled wires. Some slides were condensed, others expanded. But in many cases, the teacher talking points and even editing comments remained verbatim.

Since that summer, Halpern-Felsher hasn’t heard of any more instances of Juul’s curriculum being promoted to or used by schools. But when she goes on the road to train educators on how to counter vaping, she warns them to keep a watchful eye.

“Even if Juul is trying to do good, they should not be in the business of doing their own prevention,” Halpern-Felsher said. While she can’t say, based on what she saw, that the company was actively marketing Juul in schools, she added, “what I do know is that Juul’s curriculum was not preventing Juuling.”

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/2Mq8W0F