Reverse Engineering the BMW Connected Apps Protocol

In 2016, a BMW joined my household, and I had my first taste of IDrive and BMW Connected Apps. Through some magic Bluetooth protocol, Spotify on my phone would be added to the list of music sources in the dashboard. Clicking into this entry showed a rich user interface, offering browse options to select playlists and to start radio stations based on the current song, far more interactive than the basic Bluetooth music controls.

Excitement

This immediately ignited excitement for the possibilities! Instead of being stuck with what apps are loaded on the car at time of manufacturer, the car can automatically be upgraded as support is added to the respective phone apps. Instead of needing to take my phone out of my pocket and stare down at the phone screen to switch music, I can use the tactile controller knob with the infotainment screen to safely control any app!

Glitchy

However, as is normal with Bluetooth, the experience was not very smooth. Sometimes the additional Bluetooth Apps protocol wouldn't connect, and sometimes the individual apps themselves wouldn't be responsive. Cries for help on the Spotify forums were ignored, and the BMW Connected app has terrible reviews with no signs of fixing anything.

Other Apps

Additionally, BMW Connected for Android only shared a very limited selection of apps, compared to the available apps on iPhone: only Spotify and iHeartRadio, along with a basic Calendar app. Since I enjoy other music apps, I called up BMW Support and asked if I could get access to the BMW Ready SDK so I could build my own apps. They declined.

So, I decided to figure out this BMW Apps protocol and add my own music apps to the system, without their help.

Bluetooth Sniffing

How hard could it be? Bluetooth is a standard protocol, I just have to learn what to say to the car and build up from there!

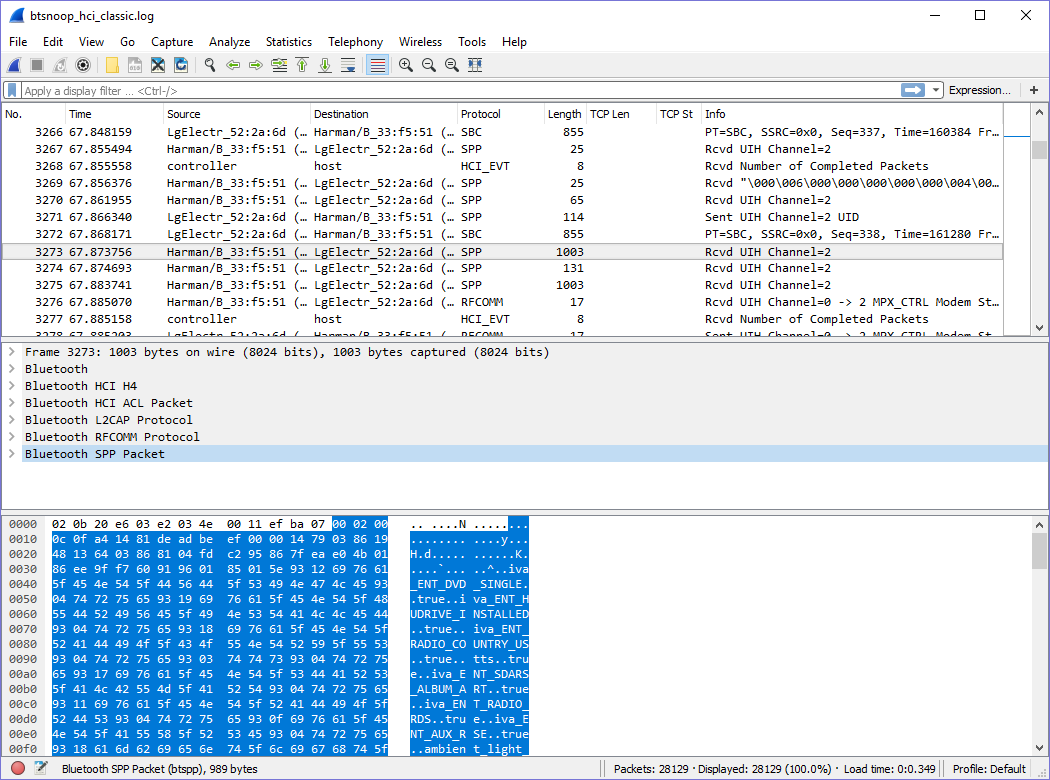

Oh hey look, Android has built-in Bluetooth Capture logging! I'll just record what the phone app is saying to the car and see what I find:

This SPP Protocol seemed to have lots of juicy information: I saw some X509 certificates, some XML data, some strings that look like song metadata, a ton of stuff!

BCL Multiplexing

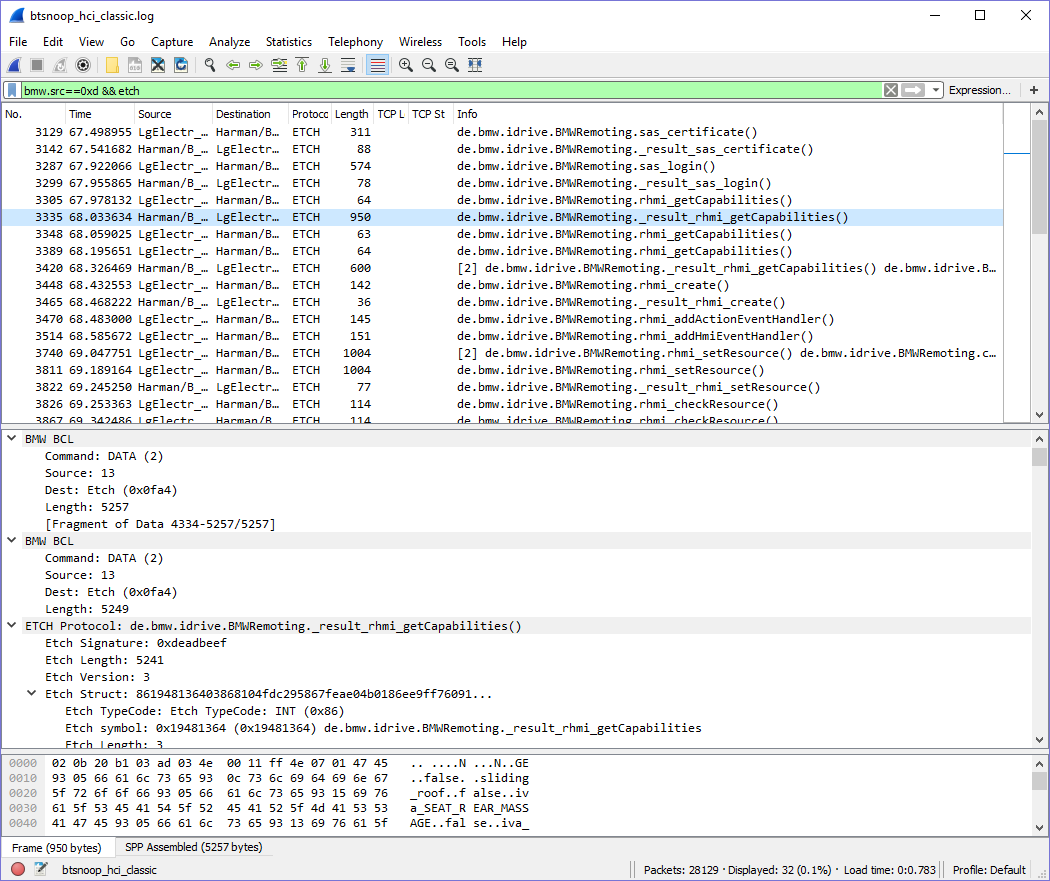

I started noticing a pattern in the first bytes of most packets: The 0th byte was 0, the 1st byte was 1 or 6, the 2nd byte was 0, the 3rd byte was usually very low, and the next bytes were almost always 0x0FA4. I figured out that the next 2 bytes were the length of the remaining data, and the next 4 bytes of data were almost always 0xDEADBEEF.

I began writing a Wireshark LUA plugin to help me understand the data, parsing the first bytes as 4 16-bit values named Val1, Val2, Val3, and Length, and then outputting the remaining bytes of data.

It seems that this protocol is used to multiplex connections into a single Bluetooth serial socket, with Val2 being different connection IDs. With this field being parsed out in Wireshark, I could use display filters to follow an individual communication flow.

Apache Etch

After a little bit of research, I discovered an article explaining that BMW uses Apache Etch as "the fundamental communication protocol used for BMW Apps". A quick trip to the Apache Etch docs confirms that 0xDEADBEEF is the magic identifier at the start of every Etch RPC call. This means, then, that I just have to decode each BCL stream to Apache Etch packets, and Wireshark's built-in Etch parsing will take over!

Apache Etch Symbol Names

Except, of course, that Apache Etch compiles each function name, and any other symbol names, into a 32-bit hash value. Wireshark can use an Etch debug artifact to replace the hash value with pretty names, but I first needed to figure out the names and hash them myself. The Etch hash algorithm is public, so I wrote a Rust implementation to help generate this debug name artifact manually, since I don't have the original Etch IDL.

But, where to get the names?

Turns out JVM bytecode (which Android apps are written in) is very easy to decompile. Variable names are obfuscated a bit, but the Etch generated classes contain an exact list of all the available Etch symbols:

ValueFactoryBMWRemoting.java: private static void a() { a = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.VersionInfo"); b = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.SecurityException"); c = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.ServiceException"); d = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.IllegalArgumentException"); e = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.IllegalStateException"); f = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.ver_getVersion"); g = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting._result_ver_getVersion"); h = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.info_getSystemInfo"); i = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting._result_info_getSystemInfo"); j = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.sas_crl"); k = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting._result_sas_crl"); l = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.sas_certificate"); m = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting._result_sas_certificate"); n = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting.sas_login"); o = (Type)hn.get("de.bmw.idrive.BMWRemoting._result_sas_login"); ... So I just run this list of names through my custom hasher, and give the resulting file to Wireshark, and get a beautiful protocol dump!

TCP Connection

While I had the decompiled code open, I poked around a little bit at the connection methods, and I discovered that the BMW Connected app runs a TCP localhost server which proxies all connections through this BCL multiplexed connection. This means that any rooted phone can run tcpdump and record every app's communication to the car, instead of running Bluetooth sniffing.

This additionally means that I don't need to rewrite the main BMW Connected app, I just need to open a TCP connection to a magic TCP port on the phone to get a direct connection to the car, and play the role of any other BMW-enabled app.

How do I find out what port the proxy is running at? The BMW Connected app broadcasts a system-wide Android Intent with the connection details to use whenever the car connection is made. Additionally, it's hardcoded to a specific port, so I could just try to connect to the port manually.

This completely changed my approach: All I had to do is learn to talk this high-level RPC protocol!

Reconstructed Etch IDL

Using the generated Etch RPC classes from the app, I was able to reconstruct an Etch IDL file, at least with the interesting bits I wanted. The Etch compiler happily accepted it and gave me back some proxy objects, even in the correct package layout as compared to my example.

Armed with my own set of Etch RPC classes, I could start poking things!

Fake Car

One of my first intrusive investigation techniques was to implement the server side of the Etch RPC and then send my own connection announcement to the official app. Android Intents are the standard way for app components to talk to each other with loose coupling, and are entirely unauthenticated. This tricked the official app modules into connecting to my own Etch server under my control, instead of the BCL proxy to the car.

The Etch objects are stubbed out with NotImplementedExceptions, so it was very easy for me to watch which calls the official apps make. After filling out as much Fake Car as I needed to make the official app happy, the app (running inside an emulator) used the provided VIN number to download an image of the car it has never been physically connected to:

The first use of this fake car was to help investigate the expected responses to the authentication challenges.

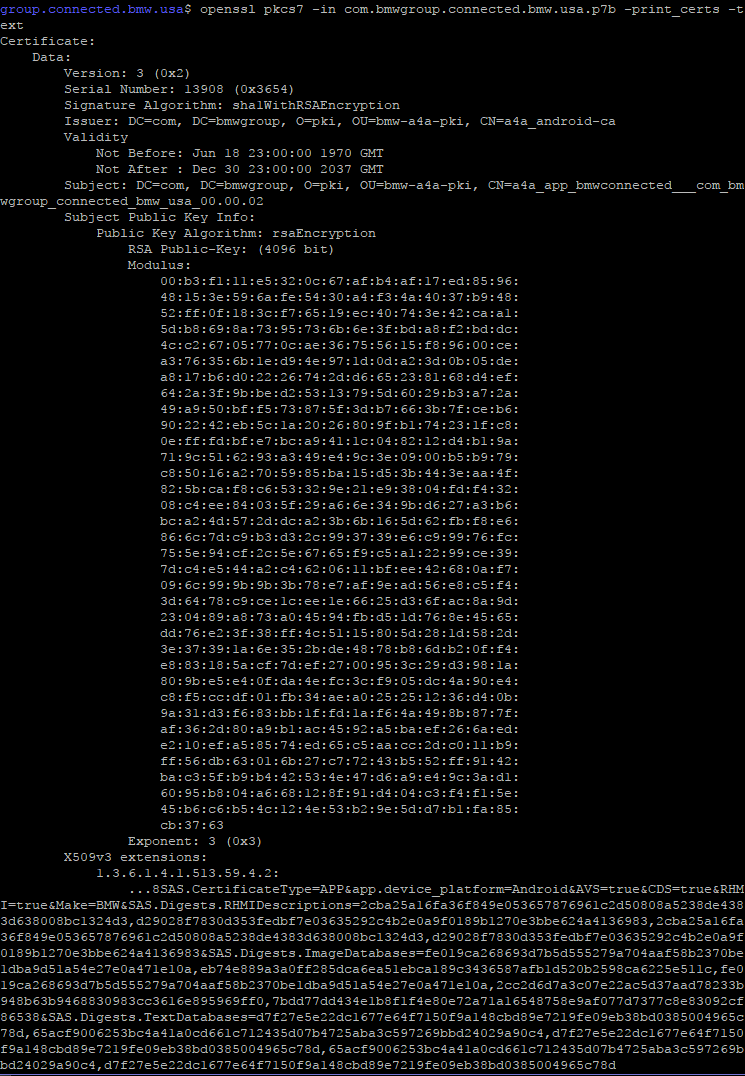

Car Authentication

When a new Etch connection is made from an app to the car, the first thing it does is send a PKCS7 certificate to the car. The car responds with a nonce, and the app is expected to respond with some authentication data.

The certificate is signed by a BMW CA, so there's no real way to get around that. However, these certs are easily available just by extracting files from app APKs, and the main Connected app includes about 10 of them.

Next, how will I figure out the proper nonce response? It looks long enough to be an RSA4096 signature, which would not be fun to try to crack.

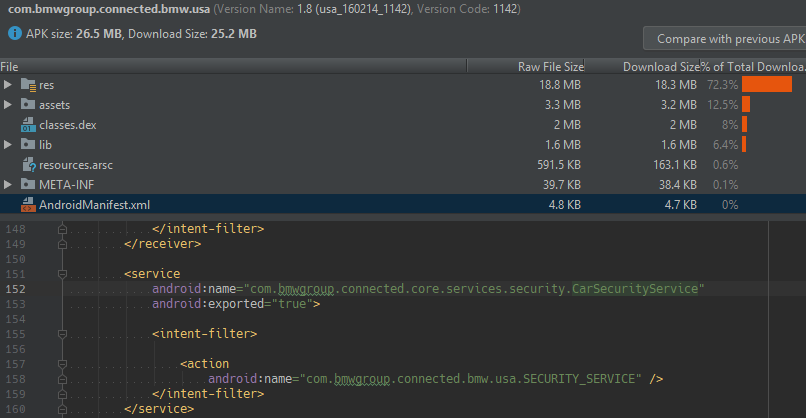

Turns out JVM bytecode is very easy to decompile: After you decompile the entire app into obfuscated Java files, you can load the entire thing into Android Studio and use its strong code search and refactoring tools to help navigate the code. Perhaps a clue can be found in com.bmwgroup.connected.internal.security.CarSecurityManager?

Yes actually, the code clearly shows how it uses Android Binder RPC to connect to a CarSecurityService object and exchange a challenge nonce for a challenge response. Additionally, this service is exported for any app on the phone to use.

Some quick test code verified that this service gives back the same answer as the Wireshark captures. The service implementation is a small JNI wrapper around a native library that suspiciously contains some OpenSSL symbols. Just for fun, I also wrote my own minimal service implementation around this library for convenience.

First Connection

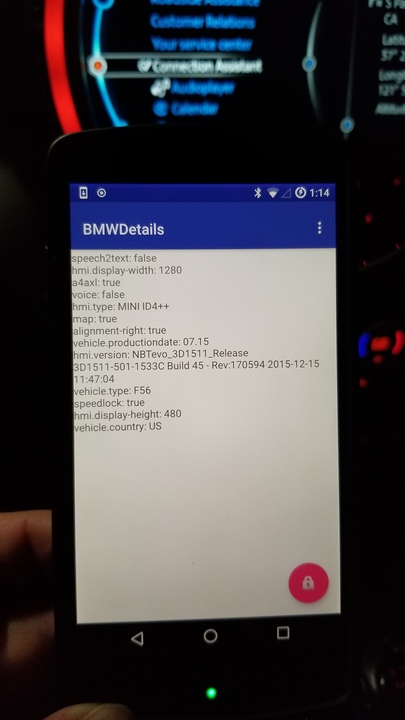

Armed with this knowledge, I quickly built a test app to try to make my first connection to the car! One of the first things the official apps do, from looking in the packet captures, is call rhmi_getCapabilities to get a list of feature flags that the car supports, which seemed like a good first step to try to implement.

This involved implementing a BroadcastReceiver to listen for the car's connection announcement, acting as a client to the SecurityService to be ready for the challenge nonce, and actually instantiating the Etch proxy objects with the proper connection details.

After several trips between my desktop and the garage, I got a successful connection!

RHMI Resources

My primary goal of this project was to add more music apps to the car, so my attention was naturally drawn to the RHMI namespace of calls, with enticing names like rhmi_setData and rhmi_onActionEvent. One of the first couple calls an app does is rhmi_setResource, which is used to send an XML widget layout and some zip files. These resources are readily available in any BMW app's APK, lending themselves to easy examination.

The first, and most important, is the XML widget layout. It contains a list of components organized into windows, and a list of models shown in the components, and a list of actions linked to the widgets. Some of these models can hold arbitrary data from the phone app, while some hold numeric IDs pointing to resources from the zip files.

The zipped resources are simple: A graphics pack, with each file inside named by a numeric ID, or a translation text pack with strings keyed by ID. Looking around in the apps, there are different resource packs for BMW or Mini brands.

First App

So, as my first attempt to create an app in the car, I copied the initialization calls to send the remote UI resources, and then tested out the rhmi_setData call to try loading an image to the car:

Events

Figuring out the action events system was pretty easy: After calling rhmi_addActionEventHandler to signal the car to send input events, the car will begin calling rhmi_onActionEvent with details about which action fired, and this action is linked back to an originating component.

RHMI Whitelist

My next experiment was to try to edit the widget layout sent to the car. However, this immediately failed, with the car rejecting the upload with an exception. Uploading the original artifact still worked great, however.

Looking closer, I found a list of SHA256 checkums in the authentication cert, and the original resources match up to those checkums. This means that I can't change any widget layout or the graphics packs. This is mainly a problem with the

Component Properties

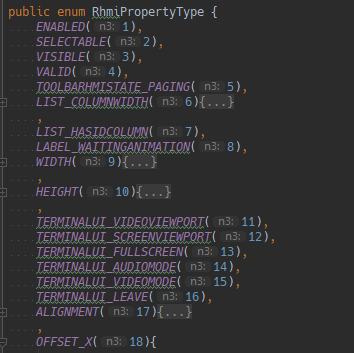

Initially I was disappointed: I wouldn't be able to build a very custom app if I'm locked into the original widget layout. However, sometimes I saw calls to rhmi_setProperty in the Wireshark captures, and some of the components in the widget layout had a

Turns out, Java bytecode is really easy to decompile, and I found this RhmiPropertyType enum that has the entire list.

So, even though I can't change the widget configuration, I can set the widget properties, including visibility, position, and size, which still allows for a ton of flexibility.

Armed with these basic building blocks, I set to work building my own music app for the car! Except I already have several excellent music apps on the phone, I would prefer to add those apps to the car instead of writing my own. Is there some way I could instead control the existing music apps?

Turns out that Android encourages music apps to implement a protocol called MediaBrowserService. By implementing this single API, the app automatically becomes available through Android Auto, Android Wear, and supposedly the Bluetooth stack. I could just act as another client to this interface, and implement the car as a frontend on top of this API.

Car App Implementation

This strategy made implementation relatively easy: I just needed to build a client to this MediaBrowserService, and whenever any metadata callbacks happen, update the car's labels with the appropriate information. Button callbacks from the car could run commands against the music app.

And then after months of polish, I have a music app with full browse and search support, which can control any MediaBrowserService music app:

Security Analysis

Is this another instance of terrible car security, letting random attackers explode your car from the other side of the world? Not at all! This is entirely separate from the Connected Drive protocol, which can be used to hack your car from the other side of the world. This Connected Apps protocol only functions over a local connection from your phone to the (running) car over USB or Bluetooth. There are a number of other security restrictions in place, to reduce the chance for mischief:

A phone app has to log in with a cert signed by BMW. However, these certs are easily accessible, just by extracting any existing app. In fact, official companion apps (such as Spotify) host a ContentProvider for the official app to fetch the app-specific certs and log into the car on their behalf. This ContentProvider provides read access to the cert for any app on the phone.

This authentication cert has a whitelist of permissions: What brand(s) of car it can authenticate in, what features it unlocks, what sections of the Car Data Service it can access, whether app creation is available or not and with what assets. However, perhaps for ease of development, the official certs are pretty much wide open, only locking down the assets to some nicely generic layouts.

The car exchanges a login nonce for the client app to sign. In 2018, BMW did remove the exported service which allowed any app to ask for the answer to this challenge. While they can't remove it from the Connected Classic app, because the Play Store won't let them update it without updating the targeted Android API level, most users will be safe, running the new Connected app. However, unscrupulous attackers could just include the JNI library to generate their own challenge responses.

The apps are sandboxed. The apps can only access information from the (read-only) Car Data Service, they don't get direct canbus access. New app layouts are hidden behind an app's entry button in the menu, and any global state is only modified through specific functions: Set the music metadata, trigger navigation, start a phone call, and not much else.

The protocol is deprecated and going away. BMW's new Live Cockpit system does not support any of this remote app protocol, instead finally adding Android Auto support to their existing Apple Carplay support. There will be some apps baked into the car, but apps from the phone won't be able to integrate in the same way.

To further reduce mischief, BMW should use their sandboxing experience and start a developer program like GM has done, for users to express their creativity and build their own apps to contribute to an app store. This entire reverse engineering project started because I wanted to add new functionality to my car, using the marvelous technology that BMW provided. The entire car modding scene shows the devotion people have for tinkering with their cars, and with cars being increasingly software-driven, this is simply the next phase of that same idea.

from Hacker News https://ift.tt/3apTHPx